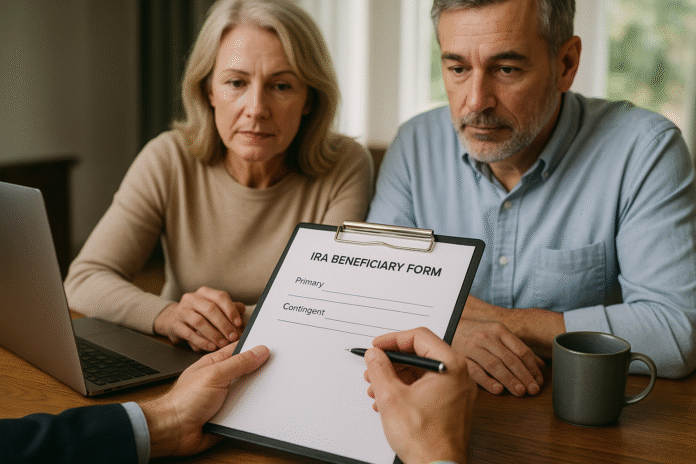

Choosing who inherits your Traditional IRA isn’t just about who you love—it controls taxes, timelines, and how smoothly assets transfer when you’re gone. In plain English: naming beneficiaries on a Traditional IRA decides who gets the money and how quickly withdrawals must happen under IRS rules. Done well, it keeps assets out of probate, preserves tax deferral, and reduces family friction. Done poorly, it can trigger accelerated taxes, delays, and legal headaches. This guide breaks down the nine considerations that matter most, with clear examples and guardrails you can use today. This article is general education only—not tax, legal, or investment advice. For U.S. readers, rules referenced are current as of now.

1. Know Your Beneficiary Types—and What Each One Triggers

The core decision is simple: name people (designated beneficiaries), and the rules are generally more flexible; name entities (like an estate or certain trusts/charities), and the payout can accelerate. After the SECURE Act, most non-spouse designated beneficiaries fall under the “10-year rule,” meaning the inherited IRA must be emptied by December 31 of the 10th year after death. Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs)—a surviving spouse, the account owner’s minor child, a disabled or chronically ill individual, or someone not more than 10 years younger than the owner—can often use a life-expectancy payout with different timing. Non-designated beneficiaries (e.g., an estate or charity) face either a 5-year rule or a “ghost” life expectancy, depending on whether death was before or after the owner’s required beginning date (RBD).

1.1 Why it matters

- People (designated beneficiaries) typically get better tax timing than entities.

- EDB status can lengthen deferral; losing it (e.g., a child reaches majority) may start a 10-year clock.

- Entities like an estate usually mean faster payouts and probate involvement—often worse for taxes and timelines.

1.2 Numbers & guardrails

- 10-year rule: Empty by December 31 of year 10; e.g., death in 2024 → deadline 12/31/2034.

- 5-year rule: Applies to non-designated beneficiaries when death is before RBD.

1.3 Common mistakes

- Assuming “designated” includes a trust or charity by default (it doesn’t unless the trust meets “see-through” rules).

Bottom line: Identify whether your named beneficiary is an individual, an EDB, or a non-designated entity. That one choice determines the tax timeline and distribution options.

2. Spousal Options—and Community Property Rules—Deserve Special Care

If your spouse is the beneficiary, they get unique, valuable choices. A surviving spouse can treat the IRA as their own (often best when the spouse is younger than the deceased) or keep it as an inherited IRA. If the deceased died before RBD, a spouse can often delay RMDs until the deceased would have reached RMD age. In contrast, non-spouse beneficiaries do not have this “treat as own” option. Also, if you live in a community property state, your spouse may have rights to part of your IRA depending on when and where assets were accumulated—this can affect whom you’re allowed to name without consent.

2.1 How to do it

- Choose the spousal path:

- Treat as own when the survivor is younger or won’t need funds for a while.

- Inherited IRA when the survivor is near RMD age or wants earlier penalty-free access.

- Mind the RBD: Age 73 is the RMD age (increasing to 75 in 2033 under SECURE 2.0); first RMD can be delayed to April 1 of the year after turning 73.

- Check community property: In AZ, CA, ID, LA, NV, NM, TX, WA, WI, spousal rights can affect beneficiary choices. Get consent where required.

2.2 Mini-checklist

- Confirm marital domicile and years lived in a community property state.

- Document spousal consent if naming someone else (your custodian may require it).

- Coordinate the IRA form with your will/trust to avoid conflicts.

Bottom line: Spouses have unique flexibility—but in community property states, you may need spousal consent to name someone else. Align your paperwork with state law and your timing needs. Ascensus

3. Naming Children—Especially Minors—Calls for Extra Structure

You can name minor children directly, but minors cannot manage inherited IRAs. Often a custodian/guardian must be appointed, or better, a trust is used to control timing and protect funds. A minor child of the account owner can be an EDB and use life-expectancy payouts until reaching the age of majority; afterward, a 10-year clock begins, with special rules in multi-beneficiary scenarios. The final regulations clarify that for SECURE purposes, majority is age 21. Consider how distributions during school years, college aid, or special-needs planning will be affected.

3.1 Tools & examples

- Option A: Direct designation + UTMA/UGMA custodian (simpler, less control).

- Option B: Conduit or accumulation trust (more control; may preserve benefits or pacing).

- Example: Parent dies in 2024 leaving IRA to a 12-year-old. Child takes annual life-expectancy RMDs until age 21, then must empty the remainder by the end of the year that includes the 10th anniversary of reaching 21 (i.e., by Dec 31 of the year they turn 31).

3.2 Common mistakes

- Naming a minor directly without naming a custodian/guardian or trust, forcing a court appointment and delays.

- Assuming “age of majority” is your state age; for SECURE EDB purposes it’s 21 under the final regulations.

Bottom line: For minors, build a management plan (custodian or trust) and remember the age-21 rule that flips the EDB switch and starts the 10-year countdown.

4. Using Trusts as Beneficiaries: See-Through Rules, Control, and Trade-Offs

Trusts can be excellent when you want control (e.g., pacing distributions, protecting vulnerable heirs, or coordinating with special-needs planning). To get the better IRA timing, your trust generally must qualify as a see-through (look-through) trust so individual trust beneficiaries, rather than the trust entity, count for RMD purposes. The final regulations retain and refine see-through mechanics and clarify documentation and beneficiary-counting rules, including special treatment for multi-beneficiary trusts with disabled/chronically ill beneficiaries.

4.1 Why it matters

- Conduit trust passes IRA distributions out to the beneficiary; accumulation trust can retain them (but may face compressed trust tax brackets).

- Documentation rules and who “counts” in the trust can change the distribution timeline; for certain multi-beneficiary trusts, only specific beneficiaries are considered for age testing.

4.2 Numbers & guardrails

- If a minor child EDB takes life-expectancy payouts, the 10-year period begins at majority; special rules coordinate when multiple minor children are beneficiaries (the clock can be keyed to the youngest).

- Plans/custodians may ask for trust details; keep the trust updated and consistent with the beneficiary form.

Bottom line: Trusts can add control and protection, but you must draft and title carefully so the trust qualifies as see-through and achieves the timeline you intend.

5. “Per Stirpes” vs. “Per Capita,” and Why Contingents Matter Just as Much

If a named beneficiary dies before you, how their share passes is a design choice. Per stirpes sends a deceased beneficiary’s share down their branch (e.g., to their children). Per capita redistributes that share among surviving beneficiaries at the same level, which can accidentally disinherit grandchildren. Your beneficiary form can also name contingent beneficiaries (Plan B) to prevent the IRA from defaulting to your estate.

5.1 How to do it

- Add contingents for every primary.

- Choose per stirpes if you want a deceased child’s share to pass to your grandchildren.

- Choose per capita if you prefer equal shares among those alive at your death.

5.2 Mini case

- You name three adult children, per stirpes, with equal shares. One child predeceases you, leaving two kids. At your death, that one-third passes to those two grandchildren instead of boosting the two surviving siblings’ shares—exactly as intended.

Bottom line: Spell out per stirpes or per capita and always add contingents. It’s the difference between “my branch gets my share” and “survivors split what’s left.”

6. Tax Timing After Death: The 10-Year Rule, Life-Expectancy Payouts, and Annual RMDs

Your beneficiary’s tax timeline hinges on two questions: who they are and whether you died before or after your RBD. For most non-spouse beneficiaries, the 10-year rule applies; if you died before RBD, no annual RMDs are due in years 1–9, just full payout by year 10. If you died on or after RBD, the final regulations require annual distributions to continue and the account to be emptied by year 10 (except when an EDB uses life-expectancy payouts). The IRS waived penalties on missed 2021–2024 annual distributions during the transition, with final regulations applying for years beginning 2025.

6.1 Numbers & guardrails

- RMD age: 73 (first RMD can be delayed until April 1 of the following year).

- Age of majority: 21 for the SECURE EDB minor child category.

- Non-designated beneficiaries: 5-year rule if death before RBD; “ghost life expectancy” if after RBD.

6.2 Quick example

- Owner dies in 2025 after RBD; adult child is beneficiary (not EDB). The child must take annual RMDs in years 1–9 and empty the account by 12/31 of year 10.

Bottom line: Map the right rule to the right person and death timing; the distinction between before and after RBD is a big tax driver.

7. Beneficiary Forms Trump Wills—and Titling the Inherited IRA Correctly Matters

Your IRA beneficiary form is a contract with your custodian. In practice, it typically overrides your will—which is why outdated forms cause so much trouble. Also, when a beneficiary inherits, the new account should be titled to show it’s inherited and retain the deceased owner’s name (e.g., “Jane Smith (deceased 2025) IRA F/B/O Alex Smith, Beneficiary”). Proper titling helps preserve the tax status and avoids confusion.

7.1 Checklist

- Review beneficiary forms annually and after life events (marriage, divorce, birth, death).

- Confirm your custodian’s inherited IRA titling format.

- Verify that every IRA has both primary and contingent beneficiaries on file.

7.2 Common pitfalls

- Assuming your will controls the IRA; it usually doesn’t. FINRA

- Moving inherited assets the wrong way (e.g., not using trustee-to-trustee transfer).

Bottom line: Keep beneficiary forms current and insist on correct inherited IRA titling to preserve tax treatment and avoid probate detours.

8. Estate, Charity, or Trust? Understand When Non-Individual Beneficiaries Make Sense

Naming your estate as the IRA beneficiary is rarely optimal—it can force faster payouts and drag the account into probate. A charity can be a superb beneficiary for tax reasons (charities don’t pay income tax), but charities are non-designated beneficiaries, so the payout timing defaults to entity rules. A properly drafted see-through trust can balance control with favorable timelines; without see-through status, a trust is treated like any other non-designated entity. Coordinate these choices with your broader estate plan.

8.1 When it may fit

- Estate: Rarely—perhaps for short-term liquidity to pay debts/expenses, knowing the tax cost.

- Charity: For philanthropic goals; consider carving out a separate charitable share or separate IRA to simplify administration.

- Trust: For spendthrift protection, special needs, or blended families; draft to qualify as see-through if possible.

8.2 Mini-checklist

- If mixing charitable and individual heirs, consider separate IRAs so each gets the most efficient rule set.

- Confirm the trust’s beneficiary class and distribution provisions align with SECURE rules.

Bottom line: Entities change the tax clock. Use them deliberately and design around their default payout rules.

9. Protecting Inherited Assets, Fixing Mistakes, and Building an Update Rhythm

Inherited IRAs don’t have the same bankruptcy protections as your own retirement funds—Clark v. Rameker held that inherited IRAs aren’t “retirement funds” for bankruptcy exemption purposes. That reality, plus family dynamics, is why many people use trusts for creditor control. Also, if life changes or you spot an error, you may be able to use a qualified disclaimer—an irrevocable refusal to accept all or part of an inheritance—if you act within 9 months and follow strict rules. Finally, set a simple annual routine for reviewing and updating every IRA form. Oyez

9.1 Tools & timelines

- Clark v. Rameker (2014): Inherited IRAs aren’t exempt “retirement funds” in bankruptcy—plan accordingly.

- Qualified disclaimer: Must be in writing and generally delivered within 9 months; handled under federal tax rules and state law formalities.

9.2 Annual audit (15-minute ritual)

- Confirm primary and contingent beneficiaries on each account.

- Re-read titling instructions at your custodian for inherited accounts.

- Log domicile (community property?) and any life events since last review.

- Note RBD-related changes (e.g., turned 73 this year?) for your spouse’s scenario.

Bottom line: Use trusts for protection when needed, know the 9-month disclaimer window, and make beneficiary reviews a yearly habit to keep your plan future-proof.

FAQs

1) Do beneficiary designations really override my will?

Usually yes. Beneficiary forms are contractual and typically control who receives IRA assets, even if your will says otherwise. That’s why keeping forms updated after life events is crucial. Financial regulators emphasize that transfer-on-death/beneficiary paperwork can supersede will provisions.

2) What’s the quick definition of the 10-year rule?

If a non-spouse beneficiary isn’t an EDB, they must empty the inherited IRA by December 31 of the 10th year after death. If death occurred before the owner’s RBD, no annual RMDs are required in years 1–9; if death occurred on or after the RBD, final regulations require annual distributions and full payout by year 10.

3) Who qualifies as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary (EDB)?

An EDB is the surviving spouse, the account owner’s minor child (until majority), a disabled or chronically ill individual, or someone not more than 10 years younger than the owner. These categories have special payout options, including life-expectancy schedules.

4) For EDB minor children, what counts as the age of majority?

For SECURE Act beneficiary rules, the final regulations set majority at age 21. When the child hits 21, a 10-year payout clock begins for any remaining balance (with special rules when multiple minor children are beneficiaries).

5) What happens if I name my estate as beneficiary?

Expect faster payout requirements and probate involvement. Non-designated beneficiaries like estates face the 5-year rule (if death was before RBD) or a ghost life-expectancy payout (if after RBD). This is usually less flexible than naming individuals or a qualifying trust.

6) I live in a community property state. Can I list someone other than my spouse?

Often yes, but your spouse may have a community property interest in IRA contributions accrued during marriage. In many such states, custodians require spousal consent to name someone else. Check state law and your custodian’s procedures. IRS

7) What are the spousal options after I die?

A surviving spouse can generally treat the IRA as their own, or keep it as an inherited IRA and use special timing rules—especially when the deceased died before RBD. Choosing between these paths depends on age, cash-flow needs, and tax planning. IRS

8) Should I use per stirpes or per capita?

Per stirpes directs a deceased beneficiary’s share down that beneficiary’s branch (e.g., to grandchildren). Per capita redistributes among survivors at the same generation level. Pick one intentionally and pair it with contingent beneficiaries to avoid defaulting to your estate.

9) Do I need a trust as beneficiary?

Not always. A see-through trust can add control and protection (e.g., for special-needs or spendthrift heirs), but it adds complexity and must be drafted to qualify for look-through treatment. If it doesn’t qualify, it may face entity payout rules. Federal Register

10) Are inherited IRAs protected in bankruptcy?

No—the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that inherited IRAs are not “retirement funds” entitled to the usual bankruptcy exemption. If creditor risk is a concern, discuss trust strategies with counsel.

11) Can a beneficiary disclaim an inherited IRA share?

Yes. A qualified disclaimer is an irrevocable refusal, generally requiring written notice delivered within 9 months and other formalities. A proper disclaimer lets assets pass as though the disclaimant predeceased, often to contingents.

12) What’s the RMD starting age now, and why does it matter for beneficiaries?

For owners, the RMD age is 73 (as of now). Whether the owner died before or after that RBD is key: it determines whether beneficiaries must take annual distributions in addition to meeting the 10-year deadline.

Conclusion

Designating beneficiaries on a Traditional IRA is one of the highest-leverage moves in your entire estate and tax plan. The person or entity you name determines who gets the account and how it must be distributed—which is another way of saying it determines how much flexibility and tax deferral your heirs will have. Start by getting the taxonomy right (designated vs. eligible designated vs. non-designated), then layer in the details that match your family dynamics: spousal options, minor children, special-needs considerations, and whether a trust is appropriate. Write “per stirpes” or “per capita” deliberately, add contingents everywhere, and keep forms synced with your will and trust so your intent is honored. As regulations evolve, a simple annual review keeps everything aligned—forms updated, titling confirmed, and timing rules (RBD, 10-year clock) understood. If your situation is complex—community property, blended families, creditor risk—pair this checklist with professional counsel. Next step: download your custodian’s beneficiary form today, add contingents, and schedule a 20-minute annual review on your calendar.

References

- Publication 590-B: Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs) — Internal Revenue Service, March 19, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p590b.pdf

- Required Minimum Distributions (Final Regulations) — Federal Register / U.S. Treasury & IRS, July 19, 2024. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/07/19/2024-14542/required-minimum-distributions

- Notice 2024-35: Certain Required Minimum Distributions for 2024 — Internal Revenue Service, April 2024. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-24-35.pdf

- Retirement Plan and IRA Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs): FAQs — Internal Revenue Service, updated December 10, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plan-and-ira-required-minimum-distributions-faqs

- Retirement Topics — Beneficiary — Internal Revenue Service, updated August 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-beneficiary

- Publication 555: Community Property — Internal Revenue Service, December 2024. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p555

- Clark v. Rameker, 573 U.S. 122 (2014) — Supreme Court of the United States / Justia, June 12, 2014. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/573/122/

- 26 U.S.C. § 2518 & 26 C.F.R. § 25.2518-2 (Qualified Disclaimers) — Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, various dates. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/2518 ; https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/26/25.2518-2

- Plan Ahead to Smooth the Transfer of Your Brokerage Account Assets at Death — FINRA, January 17, 2023. https://www.finra.org/investors/insights/plan-ahead-transfer-your-brokerage-account-assets-death

- What Is Per Stirpes? — Nolo, February 8, 2024. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/what-per-stirpes.html

- Retirement Topics — Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) — Internal Revenue Service, example updated 2024. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-required-minimum-distributions-rmds

- Inherited IRAs—What You Need to Know — FINRA (syndicated investor education), January 3, 2017. https://syndication.finra.org/content/inherited-iras-what-you-need-know