Valuing real estate correctly is the backbone of an honest net worth statement. In plain terms, you’re estimating a property’s market value—what a knowledgeable buyer would reasonably pay a willing seller in an arm’s-length deal—then recording that figure in your personal balance sheet. For most readers, that means deriving a fair, evidence-based number using accepted approaches (comparison, income, and cost), documenting how you got there, and updating it when facts change. This guide walks you through a practical, defensible workflow. Financial content disclaimer: this article is educational and not individualized financial, tax, or legal advice.

Quick roadmap (skim-friendly):

1) Pick the basis of value and purpose. 2) Gather property facts. 3) Choose the right valuation approach(es). 4) Build and adjust comps. 5) Calculate income metrics (NOI, cap rate, GRM). 6) Run a cost approach when appropriate. 7) Reconcile the numbers into one value. 8) Reflect friction and liabilities. 9) Document assumptions and sources. 10) Record the value in your net worth and scenario-test.

Follow these steps and you’ll produce a value that stands up to scrutiny—from skeptical partners to future you.

1. Decide Your Basis of Value and Purpose

Start by stating exactly what kind of value you need and why you’re measuring it. For a personal net worth, you typically want market value or fair market value (FMV)—the estimated price between willing, informed parties in an arm’s-length transaction. That definition anchors every decision you make afterward: which data to collect, which approach to emphasize, and whether you’ll reflect selling costs or taxes. If you’re valuing a primary residence, you’ll likely lean on the sales comparison approach; for a rental, the income approach has more weight. If the property is unusual (new construction, unique acreage), you may incorporate the cost approach to cross-check. Writing your basis and purpose down isn’t paperwork for paperwork’s sake—it prevents accidental bias and keeps your final number consistent with recognized standards. Reputable frameworks define market (or fair market) value in nearly identical terms; aligning with them makes your result easier to defend.

How to do it

- State the basis: “Market value” or “fair market value,” defined as an arm’s-length price between willing, informed parties.

- Name the purpose: “Personal net worth” (not lending, not tax assessment).

- Select priority approach(es): Comparison for owner-occupied; income for rentals; cost for special cases.

- Set valuation date: The date you’re measuring—so updates remain comparable over time.

- Decide on frictions: Will you record gross market value or a number net of reasonable selling costs? Note it now to avoid mixing methods later.

Common mistakes

- Blending goals (e.g., using a lender’s conservative value for personal net worth).

- Skipping the written definition, leading to inconsistent updates.

- Using a tax assessment as market value (often misaligned).

Synthesis: A clear basis and purpose act like the legend on a map—without them, even a careful analysis can lead you somewhere you didn’t intend to go.

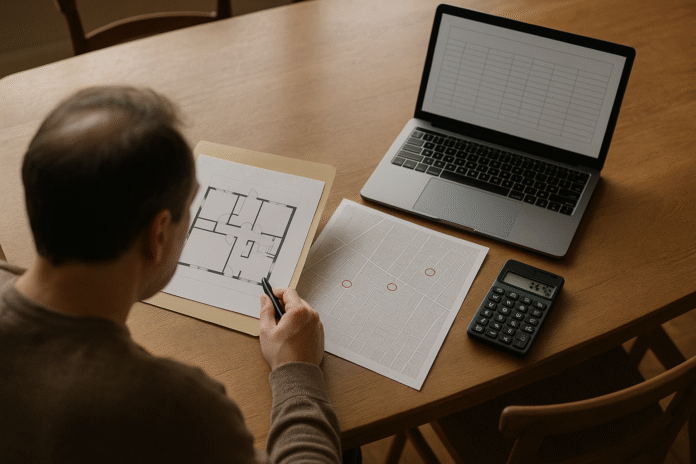

2. Gather Property Facts That Actually Move Value

Before you crunch numbers, assemble the facts that buyers and appraisers actually use to infer value. You need legal identifiers (address, parcel ID), physical characteristics (gross living area, bedrooms/bathrooms, condition/quality, renovations, lot size), zoning and permitted use, parking, views/exposure, and special features (ADU, solar, easements). Document the income profile for rentals: leases, rent roll, vacancies, and operating expenses. Verify square footage sources; living-area errors can swing values a lot. Capture whether there are concessions or atypical terms that would affect comparable sales. Using a consistent fact sheet now makes downstream comparison and adjustments clean and repeatable.

Mini-checklist (capture these before comping):

- Legal: address, parcel ID, tenure/type; any easements or restrictions.

- Physical: measured living area, bed/bath count, year of major updates, condition rating.

- Site: lot size, topography, orientation, external influences (e.g., road noise).

- Use: current use and highest and best use; zoning compliance.

- Income (if rented): current rent, typical market rent, leases, trailing 12-month expenses.

- Notes: ADU/annex, parking, storage, energy features, material defects.

Numbers & guardrails

- GLA sensitivity: In many submarkets, each 1% error in living area can roughly shift value 1% when price per square foot is a dominant metric—meaning a 150 m² (~1,615 ft²) home mis-measured by 5% could distort value by thousands.

- ADU impact: Appraisal guidance expects ADU effects to be analyzed and supported; don’t assume a 1:1 value of construction cost. Fannie Mae Selling Guide

Synthesis: Good inputs drive good outputs. A disciplined property fact pack keeps your later adjustments real, not hand-wavy.

3. Choose the Right Valuation Approach (or Mix)

There are three recognized approaches to real estate value: sales comparison, income, and cost. You’ll almost always consider more than one, then emphasize the approach that best fits your property type and data quality. Sales comparison compares the subject to recent, similar sales and adjusts for differences. Income capitalizes the property’s net operating income (NOI) using a market-supported cap rate or uses a gross rent multiplier (GRM) for quick screens. Cost estimates the land value plus current replacement cost of improvements minus depreciation. Professional standards and guides recognize all three; your job is to apply them appropriately and reconcile them coherently at the end.

How to choose

- Owner-occupied residential: Sales comparison primary; cost as a reasonableness check for newer homes.

- Small rentals: Income and sales comparison both matter; cap rate/NOI often leads.

- Unique or new construction: Cost approach helps bracket value when comps are scarce.

- Thin markets: Weigh approaches with better evidence; explain why others are downweighted.

Why it matters

Using the wrong primary approach (e.g., GRM for a luxury owner-occupied home) can produce a deceptively “precise” but misleading value. Standards expect you to state which approach(es) you used and why.

Synthesis: Pick the approach that fits the property and data—not the one that’s quickest. You’ll reconcile multiple indications later; this step sets that up.

4. Build a Clean Comparable Set and Make Defensible Adjustments

For most homes, sales comparison is king. Your goal is a set of recent, similar closed sales (ideally three or more) plus any relevant listings/pendings that bracket the subject’s value. Match on location, school catchment, property type, size, condition/quality, lot attributes, and terms (avoid outliers with heavy concessions). Once you’ve got your comparables, adjust their sale prices to reflect differences—add for superior features in the subject, subtract if the comp is better. Professional guidance stresses the need to analyze closed sales, pendings, and listings, and to adjust where concessions or atypical terms influenced price.

How to do it (practical steps)

- Screen comparables: Same micro-neighborhood when possible; similar GLA (±10–20%), lot size, bed/bath.

- Normalize terms: Identify seller credits, buydowns, or unusual financing; adjust comp prices when market evidence supports it.

- Feature adjustments: Prioritize big drivers (GLA, condition, bed/bath, parking, ADU).

- Bracket value: Ensure some comps are slightly superior and some slightly inferior to the subject.

- Weighting: Favor comparables with fewer, smaller adjustments and highest similarity.

Mini case (GLA adjustment):

- Subject: 1,800 ft²; Comp A: 1,700 ft² sold at $540,000.

- Market-supported $200/ft² for marginal living area difference.

- Size adjustment: (1,800−1,700) × $200 = +$20,000 to Comp A’s price ⇒ $560,000 adjusted.

Compact reference table (illustrative only):

| Difference | Typical adjustment logic |

|---|---|

| Living area | Market $ per additional ft²/m² (derived from paired sales) |

| Bed/bath | Local paired sales, sometimes a fixed premium per bath |

| Condition/quality | Use tiered adjustments (e.g., “renovated” vs “average”) backed by market examples |

| Garage/parking | Flat add/subtract per space, location-dependent |

| Concessions | Adjust comp’s sale price to cash-equivalent (remove seller credits, buydowns) |

Synthesis: Clean comps plus transparent, evidence-based adjustments produce a price band you can trust—and explain to anyone.

5. Calculate Income Metrics: NOI, Cap Rate, and GRM

For rentals (or homes that could rent), the income approach provides an investor’s lens. Start with NOI (Net Operating Income): gross scheduled rent minus vacancy/credit loss and operating expenses (taxes, insurance, utilities you pay, repairs/maintenance, management, HOA). Exclude mortgage payments and capital expenditures in pure NOI, but consider a reserve for replacements in practice. Then apply a capitalization rate (cap rate) from recent sales of similar properties: Value ≈ NOI ÷ Cap Rate. For quick screening, GRM (Gross Rent Multiplier) uses Value ÷ Annual Gross Rent—crude but fast. Cap rates and GRMs must be market-supported; don’t invent them.

Numbers & guardrails

- If a duplex generates $3,000/month gross and you underwrite 5% vacancy and 35% operating expenses, annual NOI ≈ $3,000×12×(1−0.05)×(1−0.35) = $22,230.

- With a local cap rate of 6.0%, indicated value ≈ $22,230 ÷ 0.06 = $370,500.

- If annual gross rent is $34,200 and market GRM is 12, GRM estimate ≈ $410,400; reconcile this with the cap-rate result by checking expense realism and comp quality.

How to do it

- Build a trailing 12-month income/expense file.

- Derive cap rates from recent, similar rent-producing sales; avoid mixing property classes.

- Use GRM only as a screen; graduate to NOI/cap rate for decisions.

- Document any reserves for replacements separately.

Synthesis: Income metrics translate rent into value. When they align with your comp-based number, confidence soars; when they don’t, dig until you can explain the gap.

6. Use the Cost Approach When It Actually Helps

The cost approach estimates what it would cost today to acquire the land and build the improvements—then deducts depreciation (physical wear, functional obsolescence, external factors). It shines for newer or special-purpose properties and as a reasonableness check for homes with few good comps. You’ll need a land value (from land sales or abstraction), a replacement-cost estimate (from a cost manual or contractor bid), and an honest depreciation figure. Guidance recognizes the cost approach as one of the three pillars; when used, state your methods and why they fit your case.

Mini case (illustrative):

- Land value from recent similar lot sales: $150,000.

- Replacement cost new (RCN) of improvements: $320,000.

- Depreciation: estimate 12% physical + 3% external = 15% total ⇒ $48,000.

- Indicated value ≈ $150,000 + ($320,000 − $48,000) = $422,000.

- If your comp-based value bands $410–430k, the cost approach corroborates your conclusion.

Common mistakes

- Confusing replacement (modern equivalent) with reproduction (exact replica); replacement is usually more relevant.

- Ignoring external obsolescence (e.g., proximity to a noisy arterial).

- Plugging “depreciation” to force a match with comps rather than deriving it from evidence.

Synthesis: Use the cost approach to cross-check or solve thin-market puzzles; it’s a guardrail, not a crutch.

7. Reconcile Multiple Indications into One Defensible Value

At this point, you may have three numbers—comparison, income, and cost—plus ranges within each. Your job is to reconcile them into one value, weighting the approaches according to relevance and evidence quality. Professional guidance expects a clear reconciliation: explain which approach dominated and why, and how you weighed individual comparables or cap-rate observations. A concise paragraph does the trick; avoid averaging blindly. If your income indication relies on thin rent data, give it less weight; if comps required large adjustments, say so and lean on the approach with fewer assumptions. Appraisal practice explicitly calls for this kind of reconciliation and rationale.

Numbers & guardrails (example):

- Sales comparison (3 tight comps, small adjustments): $560–575k, median $568k.

- Income approach (NOI $31,200; cap rate 5.75–6.25%): $499–543k, midpoint $521k.

- Cost approach (newish build, well-supported RCN): $555k.

- Reconciliation: Emphasize sales comparison (best evidence) with support from cost; acknowledge income result is lower due to current below-market rents; final opinion: $560k.

How to write it (template):

- “Given [property type/use], the sales comparison approach receives primary weight because [comparable similarity, low adjustments]. The income approach is supporting; rents are [below/at] market, cap rates drawn from [sources]. The cost approach is used as a reasonableness check. Final value reflects the tight comp band.”

Synthesis: Reconciliation turns analysis into a single, defensible number—and shows your logic, not just your math.

8. Reflect Selling Frictions, Debt, and Taxes (for Net Worth Accuracy)

A net worth statement can record gross market value or a net, realizable figure after expected selling costs (brokerage, transfer taxes, typical fix-ups). Both are acceptable if you’re consistent. For investment property, your net worth should also reflect debt and, if you prefer a “liquidation view,” likely taxes on gain. This isn’t about gaming the number; it’s about clarity. Decide your convention—e.g., “report market value and list mortgage separately” vs. “report net of estimated selling costs”—and apply it across properties. If you choose gross value, keep a note of typical selling costs so you can stress-test liquidity.

Mini case (netting logic):

- Market value (reconciled): $560,000.

- Typical total selling costs: 6–8% (commissions, transfer, staging/minor repairs) ⇒ $33,600–44,800.

- Mortgage payoff: $310,000.

- If reporting gross: Net worth entry $560,000; liabilities list $310,000.

- If reporting net of frictions: Use $560,000 − $39,000 ≈ $521,000 for asset; still list the debt separately to keep transparency.

Mini-checklist

- Pick gross vs. net-of-selling-costs convention and be consistent.

- Always record debt on the liability side.

- Note potential prepayment penalties or fees if applicable.

- For liquidation views, estimate taxes on gains separately; keep assumptions documented.

- Don’t net taxes into the market value itself—keep the value clean and add footnotes.

Synthesis: The value is the value; frictions and liabilities are separate levers. Clarity here keeps your balance sheet honest and comparable across time.

9. Document Assumptions, Sources, and Methods (Audit-Ready)

For a value to be defensible, you must show how you got there. Good documentation includes: your stated basis of value and purpose, the valuation date, the approach(es) you used and why, the comparable set with adjustment notes, the income worksheet (NOI, cap rate sources), any cost approach inputs, and a brief reconciliation paragraph. Professional valuation standards clearly expect the valuer to state approach(es) used and the rationale, summarize research, and include why other approaches were accepted or rejected. Borrow that discipline for your personal file—it takes minutes and pays off when you revisit the number later. RICS

Mini-checklist (what to save)

- One-page summary: basis, purpose, valuation date, final value.

- Comp sheet: addresses, key metrics, your adjustments, and notes on concessions.

- Income sheet: rent roll, vacancy assumption, operating expense detail, cap-rate comps.

- Cost sheet: land value evidence, replacement cost source/method, depreciation logic.

- Reconciliation paragraph with weighting rationale.

Tools/examples

- Spreadsheet with tabs for Comps, Income, Cost, and Reconcile.

- A shared drive folder with PDFs/screenshots of sales, listings, and rent comps.

- A simple template that you update on a consistent schedule.

Synthesis: Documentation isn’t busywork—it’s how you transform a one-off estimate into a repeatable valuation process that you (and others) can trust.

10. Record the Value in Your Net Worth and Scenario-Test

Now convert your reconciled value into an actionable entry. In your net worth tracker, list the property with its market value, then list the mortgage(s) as liabilities. Add a footnote that names your valuation date, basis, and a one-line description of your method (“sales comparison weight; income/cost as support”). Finally, stress-test: if rents dropped by 5% or cap rates widened by 0.5 percentage points, how would your value move? Doing this once creates quick intuition for risk and liquidity—and it helps you decide when to update the valuation (e.g., after a major renovation, lease rollover, or notable market shift).

Numbers & guardrails (sensitivity):

- Current NOI $31,200 at 6.0% cap ⇒ $520,000.

- If cap rates widen to 6.5% with same NOI, value ≈ $480,000 (about −7.7%).

- If rent drops 5% and expenses rise 2%, NOI might fall ~$2,000–3,000, shaving $30,000–50,000 off value at the same cap—worth noting in your risk notes.

Mini-checklist

- Record value and liabilities on the same update date.

- Keep a short change log: “Updated comps; renovated kitchen; new lease at $X.”

- Set triggers for re-valuation (e.g., lease renewal, refinance, remodel).

- Preserve your last valuation file so you can compare assumptions over time.

Synthesis: Putting the number on your balance sheet is step one; knowing how it can change is what turns a static tally into a living financial tool.

FAQs

1) What’s the difference between market value and fair market value?

Both terms point to the price a property would exchange for between willing, informed parties acting without pressure in an arm’s-length situation. Different standards bodies use slightly different labels, but the core idea is the same. In practical terms for net worth, you can treat them as synonymous if you define and apply the concept consistently.

2) Can I just use my property tax assessment as my value?

Usually not. Assessments serve taxation rules and can diverge from market value due to jurisdictional methods, caps, and timing. Use assessments as a data point, not the answer. Anchor your value to comparable sales and, for rentals, income metrics. When in doubt, explain why you deviated from the assessment in your notes.

3) How recent should comparable sales be?

Aim for the most recent closed sales that truly match the subject. Markets vary, but the closer in time and similarity, the better. Include active listings or pendings as supplemental context; the core of your analysis should still rely on closed sales and properly adjusted differences.

4) What if I can’t find perfect comps?

Perfection isn’t required. Pick the best available and adjust transparently. If adjustments get large or speculative, broaden the radius carefully, consider time adjustments supported by market data, and use income or cost approaches as cross-checks. Explain your trade-offs in the reconciliation.

5) Should I include selling costs in my value?

Decide on a convention and stick with it. Many people record market value on the asset side and list mortgage(s) as liabilities; selling costs are tracked separately or used in a liquidation scenario analysis. Consistency over time is what keeps your net worth meaningful.

6) How do I pick a cap rate?

Start with recent sales of similar properties and back out implied cap rates (NOI ÷ sale price). Cross-check with reputable market commentary and make sure you’re comparing like-for-like (location, asset class, condition, lease profile). Document your sources next to your NOI sheet.

7) Is GRM reliable for valuing rentals?

GRM is a quick screen that ignores expenses; use it to narrow options, then graduate to NOI and cap rates for an actual value conclusion. If GRM and cap-rate values disagree wildly, your expense assumptions or rent normalization likely need a second look.

8) Do renovations add dollar-for-dollar value?

Rarely. Market value recognizes what buyers will pay, not what you spent. Some projects (e.g., a second bathroom) can move value significantly; others (high-end finishes above neighborhood norms) may under-return. Use comps that include similar renovations and adjust based on paired sales evidence.

9) When should I update my property’s value in my net worth?

Update when something material changes: a major renovation, a new lease at a different rent, a noticeable shift in local sale prices, or when you refinance. Many people also set a recurring cadence (e.g., semiannual) so updates don’t drift.

10) Do I need a professional appraisal for my net worth?

Not necessarily. A carefully executed homeowner analysis can be solid for personal planning. However, for lending, legal disputes, or complex properties, a credentialed appraiser operating under recognized standards (e.g., USPAP) is appropriate.

Conclusion

A trustworthy real estate value for your net worth doesn’t require guesswork or proprietary magic. It requires a clear basis of value, the right approach for your property type, clean evidence (comps, income, and cost inputs), and a transparent reconciliation that anyone can follow. Most of the heavy lifting is front-loaded: building a property fact pack, selecting tight comparables, getting NOI right, and documenting your logic. Do that once and you’ll have a reusable framework you can refresh whenever conditions change. The payoff is bigger than a single number: it’s the confidence to make decisions—borrowing, renovating, refinancing, or selling—because you understand the drivers under the hood.

Ready to put this into practice? Open a fresh worksheet, start your property fact pack, and work through the 10 steps—your most accurate net worth is one methodical session away.

References

- Publication 561: Determining the Value of Donated Property. Internal Revenue Service. Publication date: 12/2024. IRS

- IVS 104: Bases of Value. International Valuation Standards Council. Publication date: 2016-04-07. IVSC

- RICS Valuation – Global Standards (Red Book). Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. Publication date: 2022-01-31 (effective date indicated in document). RICS

- Sales Comparison Approach Section of the Appraisal Report. Fannie Mae Selling Guide B4-1.3-07. Publication date: (page currently maintained without explicit date on page). Fannie Mae Selling Guide

- Adjustments to Comparable Sales. Fannie Mae Selling Guide B4-1.3-09. Publication date: 06/04/2025. Fannie Mae Selling Guide

- Valuation Analysis and Reconciliation. Fannie Mae Selling Guide B4-1.3-11. Publication date: (page currently maintained without explicit date on page). Fannie Mae Selling Guide

- Cap Rates, Explained. JPMorgan Chase Commercial Term Lending. Publication date: (page currently maintained without explicit date on page). JPMorgan

- What is a Gross Rent Multiplier (GRM)? JPMorgan Chase Commercial Term Lending. Publication date: 10/15/2024. JPMorgan

- USPAP® – Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice. The Appraisal Foundation. Publication page (ongoing). The Appraisal Foundation

- Comparable Evidence in Real Estate Valuation. Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. Publication date: 2022-01-01 (document indicates applicability around Red Book standards). RICS