Dividend investing is a simple idea with surprisingly deep mechanics: you buy shares of profitable companies and funds that regularly distribute part of their earnings to you, then you let those cash flows compound or cover bills. In practice, dividend investing works best when you blend income with total return (price appreciation plus distributions) and pay attention to taxes, diversification, and dividend safety. This guide walks you through a complete process—strategy first, then tools—so you can build passive cash flow that’s durable across markets. Quick note: this is education, not individualized advice; consider talking with a qualified financial professional about your situation.

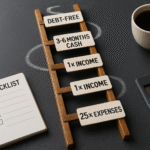

Fast definition: Dividend investing is an approach that favors businesses and funds that pay recurring cash distributions, using metrics like yield, payout ratio, and dividend growth to assess sustainability. At a glance plan:

1) set an income target; 2) choose tax-smart accounts; 3) learn key dividend dates; 4) pick a core ETF; 5) screen individual stocks; 6) favor dividend growth; 7) stress-test safety; 8) decide on DRIP vs cash; 9) avoid common traps; 10) monitor and rebalance.

Follow these steps and you’ll know what to buy, how much to expect, and how to keep the checks coming without taking unnecessary risks—and that’s the real outcome you’re after.

1. Define your income target and timeline

Start by translating “I want passive income” into a specific monthly or annual cash-flow number and a time horizon. That target shapes your expected yield, savings rate, and the mix between dividend funds and individual stocks. If you’re early in your journey, dividend income will start small; the engine is reinvestment and raises from dividend growers. If you’re closer to spending, reliability matters more than headline yield. A clear target also keeps you from chasing risky payouts, because you’ll know whether a portfolio yield of, say, 3% or 4% actually covers your goal at your current capital base. Your timeline determines whether you emphasize accumulation (reinvest via DRIPs) or distribution (collect cash and manage taxes).

Numbers & guardrails (mini case):

Suppose you want $1,000/month ($12,000/year) in dividends.

- At a 3% portfolio yield, you’d need roughly $400,000 invested.

- At 4%, about $300,000.

- At 5%, about $240,000.

Higher yields can look tempting, but they often come with lower growth or higher cut risk. Many investors blend a core yield (2.5%–3.5%) from diversified funds with select higher-yield holdings to reach the target while keeping risk in check (opinion).

Mini-checklist:

- Set a specific annual income number.

- Choose a target portfolio yield range to reach it.

- Decide accumulate vs. distribute mode for the next few years.

- Write a one-line risk statement (e.g., “No single stock over 5% of income”).

Wrap this section by committing your numbers to paper. It’s easier to ignore clicky high-yield pitches when you’ve already done the math for what you actually need.

2. Choose the right accounts and tax strategy

The same dividend can be worth different amounts after taxes depending on where you hold it. In the U.S., qualified dividends may receive favorable tax rates if holding-period and issuer rules are met, while ordinary (non-qualified) dividends are taxed at regular income rates. REIT distributions are often not “qualified,” but a portion may be treated as Qualified REIT Dividends eligible for a deduction under Section 199A; your Form 1099-DIV breaks this out. Holding period matters too: to count as qualified, you typically must hold shares for more than 60 days within a 121-day window centered on the ex-dividend date (see IRS examples). Your broker’s tax forms will categorize dividends for you each year.

How to decide account placement (opinion):

- Put tax-inefficient payers (REITs, high turnover funds) in tax-advantaged accounts when possible.

- Hold qualified dividend payers in taxable if you benefit from favorable rates.

- Use tax-advantaged accounts (IRA/401(k)/similar) for reinvestment of higher yields to compound pre-tax.

Numbers & guardrails

- If your plan relies on qualified rates, do not trade in and out near ex-dates; you can accidentally miss the holding-period requirement. The IRS examples show that missing 61 days out of the 121-day window disqualifies otherwise “qualified” amounts. Keep a buffer beyond 61 days to be safe.

Close by writing a two-line asset-location plan: which account holds your REIT exposure, which holds your dividend growth ETF, and how you’ll handle reinvestment vs. cash in each.

3. Learn the dividend mechanics and key dates

To actually receive a dividend, you need to own the shares before the ex-dividend date; if you buy on or after the ex-date, the seller gets the distribution. Companies also set a record date (who’s on the books) and a payment date (when cash hits). Stock prices commonly drop by roughly the dividend amount on the ex-date, so buying “for the dividend” isn’t a free lunch; you’re usually just converting part of your capital into cash. In rare cases of large special dividends (≥25% of price), exchanges use different timing rules for the ex-date. Understanding these mechanics prevents disappointment and keeps your logs accurate.

How to track them

- Your broker’s calendar will show declared, ex-, record, and pay dates.

- Create a simple spreadsheet with columns: Ticker, Amount, Ex-Date, Pay Date, Tax Type (qualified/ordinary), DRIP?

- Note frequency (monthly, quarterly, semiannual) to smooth cash-flow projections.

Mini case: Buy 100 shares at $50 with a $0.50 dividend. On ex-date, price often opens near $49.50, and you’ll receive $50 in cash later. You’re not instantly richer; the distribution is part of total return accounting. The SEC explains these date rules clearly—bookmark it.

Bottom line: treat dividends as predictable cash accounting entries, not trading signals. This mindset reduces churn and errors.

4. Choose a diversified core with dividend ETFs

Most investors should anchor income plans with broad, rules-based ETFs before picking individual stocks. Popular approaches include dividend growers (companies that raise payouts consistently), high-yield screens, and quality-yield blends. For instance, the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats methodology selects S&P 500 members with 25+ consecutive years of dividend increases and equal-weights them; several ETFs track this index. Global “dividend growers” indices from MSCI use profitability and variability filters alongside dividend history. These guardrails help avoid yield traps and concentrate on durable cash generators.

How to pick your core ETF

- Methodology: Prefer transparent, rules-based selection with caps to avoid sector over-concentration.

- Yield vs. growth: Decide if you want a higher starting yield or faster dividend growth; many blend one of each.

- Costs & turnover: Lower expense ratios and sensible rebalancing are your friends over long horizons.

Numbers & guardrails (mini case):

Assume two ETFs: Fund A yields 2.4% and historically grows distributions 8% annually; Fund B yields 3.6% with 3% growth. On a $200,000 allocation, first-year income is $4,800 vs. $7,200. After 10 years of the assumed growth, A pays about $10,367 while B pays $9,677 annually—illustrating why growth can catch up and surpass. (Illustrative math; check each fund’s documents for actual results and costs.)

Anchor with one or two diversified ETFs; then layer selective stocks if you want more yield, sector tilts, or tax features.

5. Screen individual dividend stocks with quality and coverage metrics

If you add single stocks, let quality and coverage lead your screen, not just yield. Start with industries that support dividends through durable cash flows (consumer staples, utilities, select industrials), then check payout ratio (dividends ÷ earnings) and free cash flow coverage. For REITs, use FFO and AFFO instead of GAAP EPS because depreciation distorts earnings; Nareit defines these non-GAAP measures and explains why they’re used. Keep an eye on leverage and interest coverage to understand resilience under stress.

Compact guardrails table

| Metric | Typical guardrail | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Payout ratio (EPS) | 30%–60% for cyclicals; up to ~70% for defensives | Very high (>100%) often signals risk without one-offs. |

| FCF payout | Prefer <70% over a cycle | Cross-check with EPS payout to catch accounting noise (opinion). |

| Debt/EBITDA | Sector-specific; lower is better | Rising rates punish high leverage (opinion). |

| Interest coverage | >4× for non-financials | Indicates room to keep paying during downturns (opinion). |

| REIT payout (AFFO) | <85% typical, with stable AFFO growth | Use FFO/AFFO, not EPS, for REIT safety. |

Tools/Examples

- Start lists from established universes like Dividend Aristocrats before deeper research.

- Read company filings for dividend policy language and DRIP notes.

- Compare 5-year dividend growth and revenue stability.

Finish by remembering: your goal is repeatable cash from repeatable business models, not the highest percentage on a quote screen.

6. Prioritize dividend growth over headline yield

Dividend growth is the quiet compounding engine of passive cash flow. Companies that raise payouts regularly often pair that policy with strong balance sheets and disciplined capital allocation. Indices that focus on dividend growth (e.g., S&P Dividend Growers, S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats; MSCI Dividend Growers) encode this discipline into their rules—requiring years of increases and other quality screens—so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Growth helps your income keep pace with inflation and can reduce the risk of cuts compared with ultra-high yielders.

Numbers & guardrails (mini case):

- Portfolio X: 3% yield, 8% dividend growth.

- Portfolio Y: 6% yield, 0% growth.

Starting at $500,000, Year-1 income is $15,000 vs. $30,000. After 12 years, X pays roughly $28,292 while Y still pays $30,000. Meanwhile, markets often reward growing cash flows with higher valuations, boosting total return (opinion).

Common mistakes

- Chasing yield without growth in cyclical businesses with thin margins.

- Ignoring payout spikes caused by one-time earnings dips.

- Overlooking sector concentration (e.g., all utilities/financials).

In short, a modest starting yield with persistent growth is usually a more resilient path to long-term income.

7. Stress-test dividend safety and cyclicality

Before you rely on a payout, ask what could break it. Start with payout ratios through a cycle, then model a revenue drop to see whether free cash flow still covers the dividend. Review debt maturities and variable-rate exposure. For REITs, analyze FFO/AFFO trends—these are the accepted non-GAAP yardsticks Nareit formalized—to gauge whether property cash flows support distributions after maintenance capex.

Numbers & guardrails (mini case)

Imagine a company that earned $5.00 EPS last year, pays a $2.50 dividend (50% payout), and generates $3.00 FCF per share. If a downturn cuts EPS to $3.50 and FCF to $2.20, the EPS payout jumps to 71% and FCF coverage falls below 1×. That’s borderline: you’d want evidence of temporary headwinds, strong liquidity, or planned capex cuts. For a REIT paying $2.00 per share with $2.40 AFFO, a 15% drop to $2.04 AFFO still covers the dividend at 98%—tight, but not necessarily a cut if the balance sheet is conservative (opinion).

Bullet guide:

- Read the dividend policy in filings and past cut history.

- Check interest coverage and debt ladders.

- Look for consistent dividend growth rather than sporadic hikes.

- Avoid names where dividends exceed FCF/AFFO for multiple periods.

- For REITs, rely on Nareit’s FFO/AFFO definitions rather than EPS.

Tie back to your goal: safety beats surprise. You can’t build a calm cash-flow plan on shaky foundations.

8. Set a reinvestment (DRIP) and withdrawal policy

A Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRIP) automatically turns your cash payouts into more shares—either through a company-sponsored plan or your broker’s service. DRIPs are fantastic during accumulation because they boost share count and income without extra trading friction. Company and broker DRIPs vary in fees and mechanics, so read the disclosures. Remember: reinvested dividends are still taxable in taxable accounts if they’re not qualified for deferral. In distribution mode, turning DRIPs off lets you collect cash and only sell shares as needed. The SEC’s Investor.gov explains DRIPs plainly; many companies describe their specific DRIPs in prospectuses.

Numbers & guardrails (mini case):

Start with $100,000 in a core dividend ETF at a 3% yield, growing 8% annually, and price appreciation of 6%.

- With DRIP: After 10 years, income roughly doubles as shares accumulate and the dividend per share rises, pushing annual income near $6,480 from $3,000 (illustrative compounding).

- Without DRIP: You’ll still see income growth from per-share increases (to about $6,480 on the original share count), but you’ll have collected $36,000+ in cash along the way.

Both paths are valid; DRIP is about accelerating compounding vs. harvesting cash.

Mini-checklist:

- Turn DRIP on in accumulation accounts; off where you plan to spend.

- Revisit annually; DRIP can hide oversized positions because it dollar-cost-averages automatically.

- Track basis on reinvested shares for taxes (your 1099-DIV reports categories).

Choose consciously: reinvest by default, unless you specifically need cash or are trimming an oversized holding.

9. Avoid common traps and timing mistakes

Dividend investing has its own potholes. The classic one is the yield trap: a high quoted yield caused by a falling stock price, often right before a cut. Another is dividend capture trading—buying right before the ex-date—despite the price typically dropping by the dividend amount on the ex-date. A third is misreading special dividends and their unique ex-date rules, which can invert the usual timing. Finally, investors sometimes forget the holding-period rule and lose qualified status through excessive churn. The SEC and IRS sources cover these mechanics in plain language; internalize them early.

Bulleted watch-outs:

- If yield spikes, ask “what changed?” before you buy.

- Don’t buy just for the dividend; price adjusts on ex-date.

- Check special-dividend rules when payouts are unusually large.

- Track holding periods if you care about qualified rates.

Mini case: You eye a $1.00 quarterly dividend with a stock at $40. Buying the day before ex-date nets $100 on 100 shares—but the price often opens near $39 on ex-date. After taxes and spreads, it’s rarely worth it unless you planned to own the business anyway. The SEC’s explanation of ex-dates illustrates why.

Takeaway: earn dividends by owning great businesses, not by gaming the calendar.

10. Monitor, rebalance, and document rules

Income portfolios need light but regular maintenance. Once or twice a year, verify that each holding still meets your quality, payout, and diversification rules. Rebalance when one sector dominates income or when a position drifts beyond your sizing limits. Keep a one-page Investment Policy Statement (IPS) for your dividend plan: income target, max position size, sell rules (e.g., two consecutive dividend cuts, payout >100% for two years, leverage above your threshold), and your rebalancing cadence. This written playbook keeps you calm when headlines get loud.

Simple sell rules (opinion)

- Dividend cut without a credible remediation plan.

- Payout coverage broken across EPS and FCF/AFFO.

- Strategic reset that eliminates the dividend in favor of growth you don’t want.

Numbers & guardrails (mini case):

Say your top three holdings generate 55% of income. Rebalance so no single name exceeds 10% of total income and no sector over 30%. After reallocating, your income may dip slightly today but becomes more resilient against a single cut tomorrow.

Finish by calendaring your next portfolio review date and saving your IPS where you’ll see it. Process beats impulse.

FAQs

How much money do I need to live off dividends?

Work backward from your annual cash-flow need and a conservative yield. If you need $24,000/year and target a 3.5% yield, plan for roughly $685,714 invested. Many investors blend a core of dividend ETFs with a few higher-yield holdings to reach the target while protecting dividend growth. Remember to account for taxes and whether dividends are qualified or ordinary.

Are dividends guaranteed?

No. Dividends are declared at the discretion of a company’s board and can be raised, paused, or cut. Look for long records of increases (e.g., 25+ years for “Dividend Aristocrats”) and strong coverage metrics to reduce cut risk, but never assume permanence. Funds tracking dividend-growth indices follow transparent rules that can remove companies after cuts. S&P Global

Should I chase the highest yield?

Usually not. Very high yields can signal distress. Favor sustainable payouts with reasonable payout ratios and evidence of dividend growth. Compare EPS payout to free cash flow coverage (or AFFO for REITs) and check leverage before buying.

What’s the difference between qualified and ordinary dividends?

Qualified dividends may receive favorable tax rates if issued by eligible corporations and if you meet holding-period rules. Ordinary dividends are taxed at regular rates. Your Form 1099-DIV shows the breakdown. If favorable rates matter to you, avoid frequent trading that resets holding periods.

Do I need to buy before the ex-dividend date?

Yes. To receive the next dividend, you must own shares before the ex-dividend date. Buying on or after the ex-date means the seller gets the dividend. Stock prices typically adjust by roughly the dividend amount on the ex-date, so short-term “dividend capture” rarely adds value.

What is a DRIP and should I use it?

A Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRIP) automatically reinvests your dividend into more shares. It’s great for accumulation and is offered by many companies and brokers. Fees and rules vary, so read disclosures; reinvested dividends in taxable accounts are still taxable. Turn DRIP off when you want to spend cash or manage position size tightly.

How do REIT dividends get taxed?

Many REIT dividends are not qualified and are taxed as ordinary income, but a portion may be Qualified REIT Dividends eligible for a deduction under Section 199A, subject to rules. Your broker reports this split on Form 1099-DIV. Consider holding REIT exposure in tax-advantaged accounts if you’re sensitive to current taxes.

Which is better: dividend growth or high yield?

Both can work; the key is sustainability. Dividend-growth strategies often deliver rising income and solid total returns, while high-yield strategies provide more cash today but can carry higher cut risk. Many investors blend them using a growth-tilted core ETF and a measured sleeve of higher-yield names. Review methodology documents to know what you actually own.

Do ETFs actually pass through dividends to me?

Yes. Dividend-focused ETFs collect distributions from their holdings and distribute them to shareholders, typically quarterly or monthly, according to fund policy. Each ETF’s prospectus explains how distributions work and how the index selects holdings.

What metrics should I use for REITs?

Use FFO and AFFO, industry measures defined and discussed by Nareit, rather than GAAP EPS. Focus on AFFO payout, same-store metrics, and debt structure. These provide a more realistic view of a REIT’s ability to sustain and grow its dividend over time.

Conclusion

Dividend investing isn’t about memorizing a list of tickers; it’s about building a system that steadily converts business profits into your cash flow while still capturing total return. Start with a clear income target, place assets in tax-savvy accounts, and understand mechanics like ex-dates and holding periods. Anchor the portfolio with transparent, rules-based ETFs and add individual stocks screened for quality, coverage, and growth. Choose a reinvestment or withdrawal policy that matches your stage, avoid common timing traps, and keep a simple written playbook with sell rules and a review cadence. Do these ten things consistently and your dividend income becomes something you can plan around—not hope for.

Call to action: Set your income target and choose your core dividend ETF today; then schedule your first portfolio review on your calendar.

References

- “Topic No. 404, Dividends,” Internal Revenue Service, Page Last Reviewed or Updated: 08-Sep-2025. https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc404 IRS

- “Publication 550: Investment Income and Expenses,” Internal Revenue Service, Feb 14, 2025 (PDF). https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p550.pdf IRS

- “Ex-Dividend Dates: When Are You Entitled to Stock and Cash Dividends?” Investor.gov (U.S. SEC), undated page. https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/glossary/ex-dividend-dates-when-are-you-entitled-stock-and

- “Direct Investing (Dividend Reinvestment Plans),” Investor.gov (U.S. SEC), undated page. https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/getting-started/investing-your-own/direct-investing

- “Instructions for Form 1099-DIV,” Internal Revenue Service, undated page (current). https://www.irs.gov/instructions/i1099div

- “S&P Dividend Growers Index Series Methodology,” S&P Dow Jones Indices, methodology document. S&P Global

- “ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats ETF – Summary Prospectus,” ProShares, latest version (PDF). ProShares

- “MSCI World Dividend Growers Quality Select Index – Factsheet,” MSCI, latest monthly factsheet (PDF). MSCI

- “Funds From Operation (FFO),” Nareit Glossary, undated page. REIT.com

- “Adjusted Funds from Operations (AFFO),” Nareit Glossary, undated page. REIT.com

- “Payout Ratios Can Reveal Dividend Stability,” Morningstar, Oct 1, 2021. https://www.morningstar.com/portfolios/payout-ratios-can-reveal-dividend-stability

- “S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats – Overview,” S&P Dow Jones Indices, undated page. S&P Global