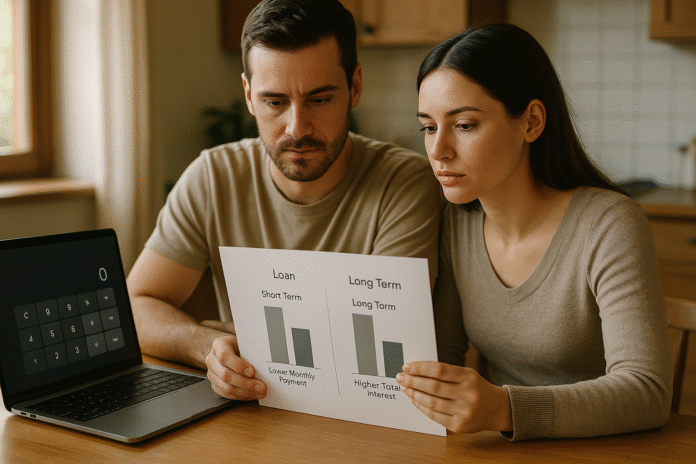

Picking a loan tenor (the length of time you take to repay) is one of the biggest levers you have over affordability and total cost. In plain terms: a longer term lowers your monthly payment but raises your total interest; a shorter term does the opposite. Within the first 1–2 minutes of reading, you’ll know how to weigh this trade-off against cash flow, risk, and your goals. This guide is for anyone deciding between short and long terms for mortgages, auto loans, personal loans, or student loans. This is educational information, not financial advice—consider speaking with a qualified adviser for your situation.

Quick take:

- Longer term → smaller monthly payment, higher total interest paid over time.

- Shorter term → bigger monthly payment, lower total interest (and you build equity faster).

- Match tenor to income stability, emergency buffer, and how long you’ll keep the asset.

- Watch prepayment rules, APR (fees), and debt-to-income guardrails.

- Revisit tenor if you plan to refinance or make extra principal payments later.

1. Understand the Core Trade-Off: Payment Relief vs Lifetime Cost

A longer loan tenor immediately lowers your monthly commitment, but it raises the cumulative interest you’ll pay; a shorter tenor does the reverse. That’s because amortized loans front-load interest when balances are highest, so stretching payments over more months increases the number of times interest accrues. This is true across mortgages, auto, and personal loans. For example, on a $25,000 auto loan at 7% APR, a 3-year term runs about $772/month and $2,789 total interest; a 5-year term drops to about $495/month but increases total interest to roughly $4,702—a $1,913 cost for the extra breathing room. If your budget is tight or variable, the longer term can create stability; if your income is strong with a good emergency fund, the shorter term saves money and builds equity faster. The right answer depends on your cash flow, risk tolerance, and how long you’ll keep the asset. In all cases, knowing the math—and your margin for error—keeps you in control. Early in a loan, more of each payment goes to interest and less to principal, which is why longer terms typically amplify total interest.

1.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Amortization effect: Interest portion starts high and falls as principal shrinks.

- Illustrative mortgage: $250,000 at 6% for 30 years ≈ $1,499/month and ≈ $289,595 total interest; 15 years ≈ $2,110/month and ≈ $129,736 total interest.

- Cash-flow vs cost: Decide how much payment relief you need and the total interest you’re willing to trade for it.

1.2 Mini checklist

- Can you afford a shorter term and keep a 3–6-month emergency fund?

- Will a longer term meaningfully reduce stress or just defer cost?

- Are you likely to sell or refinance before the term ends? If yes, total interest projections should reflect that horizon.

Bottom line: Start with the math and your margin. Lower payments help today; total interest is tomorrow’s price for that help.

2. Fit the Tenor to Your Cash-Flow Reality (and Buffer)

Choose the shortest tenor you can sustain without endangering your monthly essentials or emergency savings. Stretching too far into a short term can force you to use credit cards for surprises; stretching too far into a long term can make you complacent about total cost. A practical approach is to trial-run the payment for a month or two in your budget before you lock the term. If the short-term payment squeezes your buffer below three months of expenses, that’s a red flag. Conversely, if the long-term payment leaves you with surplus cash that will sit idle, you may be overpaying for safety you don’t need. Consider income volatility (bonuses, commissions), fixed obligations (rent, childcare), and near-term goals (moving, grad school). It’s also smart to build “payment shock” into your model—assume unexpected bills hit the same month as your first payment. Finally, remember that interest accrues monthly; every extra month on the clock adds cost, so take only as much term as you truly need.

2.1 How to do it

- Stress-test two or three terms in your budget app or spreadsheet.

- Run worst-case cash flow: What if income falls 10% for a quarter?

- Preserve liquidity: Keep 3–6 months’ essential expenses even after closing.

- Use windfalls (bonus/tax refund) as optional principal prepayments rather than betting on them for a shorter term.

2.2 Mini example

You can afford $2,000/month comfortably. A 15-year mortgage quote is $2,110; 30-year is $1,499. If the extra $611/month would drop your emergency fund from $12,000 to $5,000 within 18 months, the longer term plus planned extra payments (see Rule 5) may be wiser. You preserve resilience while still controlling lifetime cost.

Bottom line: Right-sized terms protect your buffer and prevent debt from crowding out essentials.

3. Respect Debt-to-Income Guardrails (DTI) and Affordability Ratios

Keep your total debt-to-income (DTI) in a healthy range so you can weather rate shocks (for variable loans) and life events. DTI is monthly debt payments divided by gross monthly income. Many lenders and frameworks still view 36–45% as a typical total DTI range, with program-specific caps higher in some automated underwrites. For U.S. mortgages, legacy “General QM” guidance used 43% DTI as a ceiling (though the rule basis evolved), and Fannie Mae policy allows higher DTIs in some scenarios—manual caps around 36–45% and up to 50% through Desktop Underwriter (DU), subject to risk factors. None of this replaces personalized underwriting, but it’s a reality check if your plan exceeds those bands. Use DTI early to avoid picking a tenor that passes today but strains you later. Calculate both front-end (housing only) and back-end (all debts) DTIs, and model how different tenors change them.

3.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Compute DTI: Sum monthly debt payments ÷ gross monthly income.

- Reference bands (U.S. mortgages): 36–45% typical; certain DU approvals up to 50% with compensating factors.

- Front-end ratio: Housing costs ÷ gross income (often modeled around ~28%), but program rules vary. Investopedia

3.2 Tips

- If a short term pushes your DTI from 38% to 48%, consider a longer tenor or reduce loan size.

- Don’t ignore non-debt essentials (childcare, health premiums); underwriters don’t count them, but your budget does.

- If your DTI is borderline, seek programs with compensating factors (reserves, strong credit).

Bottom line: Let DTI be a safety fence; the “right” tenor lives inside it with room to spare.

4. Run Amortization Scenarios and Compare Lifetime Costs

Before you sign, run side-by-side amortization for two or three tenors at the same interest rate. This makes the trade-off concrete—monthly payment, total interest, and the break-even if you expect to sell or refinance early. For a $250,000 mortgage at 6%: 30 years ≈ $1,499/month and ≈ $289,595 total interest; 15 years ≈ $2,110/month and ≈ $129,736 total interest. If you plan to sell in year 7, compare cumulative interest over 84 months, not the whole term. When comparing offers, also look at APR, not just the nominal rate—APR bakes in required fees and points so you see fuller cost. APR is usually higher than the note rate because it includes those charges. As of September 2025, comparing both rate and APR remains best practice, especially if you’ll hold the loan long enough for upfront points to pay off. Use reputable calculators, and save the PDF schedules for your records.

4.1 How to do it

- Request loan estimates for each tenor you’re considering.

- Enter figures in an amortization calculator; export schedule.

- Compute total interest for your expected holding period (e.g., 5–7 years).

- Compare both rate and APR across quotes.

4.2 Mini case

Two offers on $300,000: 30-yr at 6.25% APR 6.38% vs 20-yr at 6.00% APR 6.22%. If you’ll keep the loan 10 years, the 20-year schedule likely costs less interest despite the higher payment—check the 120-month cumulative columns and confirm fees via APR.

Bottom line: Model it. Tenor choice is clearer when you see payments and cumulative interest side-by-side.

5. Build in Prepayment Flexibility (and Know the Rules)

Even if you choose a longer tenor, prepaying principal can slash total interest and shorten the effective term—if your loan allows it without penalty. For instance, on a $250,000, 30-year mortgage at 6%, paying $250 extra per month can cut about 9 years and save roughly $100,000 in interest. But prepayment terms vary: in the U.S., some mortgages still include limited prepayment penalties (often within the first 3–5 years), while many government-backed loans prohibit them; always read your note and disclosure. Internationally, rules differ: in India, regulators have restricted or banned prepayment penalties for floating-rate loans to individuals, widening flexibility. If your lender offers free extra payments, you can start long for safety and self-shorten later with bonuses or raises—provided you direct overpayments to principal and keep the account current. If a penalty exists, compute whether waiting until the penalty window lapses is cheaper than paying it now.

5.1 Common pitfalls

- Sending extra money without specifying “apply to principal”.

- Assuming all loans allow partial prepayments penalty-free—check the note.

- Over-prepaying and starving your emergency fund.

5.2 Region notes (as of Sep 2025)

- U.S.: Prepayment penalties are regulated and limited; details vary by product and state; ask for disclosures and penalty periods.

- India: RBI directions prohibit/curtail prepayment charges on floating-rate loans to individuals across banks and NBFCs.

Bottom line: Flex matters. If you may prepay, pick terms (and lenders) that make extra principal easy and penalty-free.

6. Weigh Rate Outlook, Fixed vs Variable, and Refinance Plans

Tenor choice doesn’t live in a vacuum—it interacts with rate type and your view of future refinancing. If rates are high today and you believe they may fall, a longer fixed term can provide payment comfort now while preserving the option to refinance shorter later. Conversely, if you can tolerate some payment volatility, a shorter adjustable/floating period with plans to refinance can work—but only if you understand caps, reset schedules, and worst-case payment at the fully indexed rate. As of September 2025, refinancing pipelines and rate cycles vary by region; what matters is your contingency plan if rates don’t fall. Model both a high-rate “no-refi” scenario and a successful refi scenario; don’t let optimistic forecasts be the only reason for a short tenor you can barely afford. Consider closing costs: if you’ll likely refinance, paying points today for a lower rate may not be worth it.

6.1 “What if” modeling

- No-refi case: Can you sustain the payment for the full term?

- Refi case: Include closing costs, break-even months, and potential appraisal hurdles.

- Variable loans: Stress-test at the cap rate and at the long-run average.

6.2 Tools/Examples

- Ask lenders for rate/point trade-offs and “no-cost” refi options.

- Track your break-even: points paid ÷ monthly interest savings.

Bottom line: Tenor + rate strategy should survive both falling-rate dreams and stubborn-rate realities.

7. Match the Tenor to Asset Life and Your Holding Horizon

Loans should roughly align with how long you’ll keep the asset. For cars, typical terms range 36–72 months; past 84 months, vehicles may depreciate faster than you repay, raising negative-equity risk. For mortgages, if you expect to move or refinance within 5–7 years, it may not make sense to pay points for a lower rate on a very long term—compare 60–84-month cumulative costs instead. For student loans, forgiveness and income-driven plans can influence optimal tenor and prepayment strategy. If the asset’s useful life ends before the loan does, you’ll still be paying for something you no longer own or use. Conversely, a house is long-lived; a 30-year term can be appropriate if your budget needs stability, especially if you plan disciplined prepayments when income rises. When horizons are uncertain, flexibility (penalty-free prepay, easy extra payments) becomes a deciding feature.

7.1 Mini checklist

- How long will you keep/use the asset?

- What’s the resale or upgrade timeline (car replacement cycle, likely move)?

- Will program specifics (forgiveness, subsidies) change the calculus?

- Does the term outlast the warranty or service life?

7.2 Case example

A buyer expects to relocate in 6 years. A 20-year mortgage offers lower payment than a 15-year but higher monthly than a 30-year. Since they’ll hold only ~72 months, they compare cumulative interest to month 72 and find the 20-year term strikes the best balance between payment and cost, especially with penalty-free extra principal.

Bottom line: Align tenor with how long you’ll keep the thing you’re financing—not just with lender defaults.

8. Look Beyond the Rate: APR, Fees, and Insurance Can Flip the Winner

Two loans with the same rate can have very different APR because of fees and points, and APR better reflects total borrowing cost if you’ll keep the loan for a long time. With shorter holding periods, the raw rate can matter more than APR, because you might not “earn back” points. Also budget for mortgage insurance (PMI) or guaranty fees on low-down mortgages, and for gap/extended warranties in auto loans—some add to your financed balance and thus grow interest. Watch precomputed-interest products and any add-on that raises effective cost without clear value. Ask lenders for a fee itemization and a no-points vs points comparison in the same quote. If term A looks cheaper on monthly payment but carries higher APR and upfront fees, the apparent win can vanish when you compute total interest + fees over your expected horizon. As of September 2025, the definition of APR and required disclosures remain central to comparing offers.

8.1 Mini checklist

- Compare rate and APR for each tenor.

- Note upfront vs recurring costs (points, mortgage insurance).

- Don’t finance optional add-ons that don’t hold value.

- Re-run totals for your likely holding period.

8.2 Example

Offer A: 30-yr at 6.125% with $6,000 points/fees (APR 6.38%). Offer B: 30-yr at 6.375% with $2,000 in fees (APR 6.45%). If you’ll sell in 7 years, B might be cheaper despite the higher APR on paper; run 84-month totals including fees to see the real winner.

Bottom line: Tenor choice is inseparable from fees and insurance—compare the whole cost, not just the coupon.

9. Use a Simple Decision Framework (and Lock It with a Plan)

Here’s a practical method to settle on a tenor with confidence. First, define your target payment range that preserves your emergency fund and keeps DTI within comfortable bounds. Second, price two or three tenors and run amortization to see payment and total cost. Third, choose the shortest tenor that fits your budget with a buffer; if that’s still tight, select the longer tenor with an automatic extra-payment plan (e.g., $100–$300/month to principal) and ensure no prepayment penalty. Fourth, decide what might trigger a later refinance (rate drop of X%, equity milestone, credit score improvement). Finally, memorialize your plan in writing so you follow through—tenor discipline is a habit, not a guess. This framework blends affordability today with cost control tomorrow, and it’s robust to uncertainty because it embeds buffers and options.

9.1 Steps (copy-ready)

- Set a payment cap that preserves cash reserves and acceptable DTI.

- Price two or three tenors; export amortization schedules.

- Pick the shortest sustainable tenor; otherwise, pick longer + automatic extra principal.

- Verify prepayment terms and penalty windows before you rely on extra payments.

- Define refi triggers and calendar a review in 12 months.

9.2 Mini example

A borrower qualifies for $1,900/month comfort. Quotes on $250,000 at 6%: 30-yr $1,499; 20-yr $1,791; 15-yr $2,110. They pick 20 years to stay under $1,900 and set a $150 automatic principal prepayment. If income rises, they’ll increase the extra to $300, shaving years and tens of thousands in interest without risking today’s budget.

Bottom line: Decide, document, and automate. That’s how tenor choice becomes real savings.

FAQs

1) What is “loan tenor,” and how is it different from “term” or “tenure”?

They all refer to how long you’ll take to repay the loan. “Tenor” and “tenure” are often used interchangeably with “term” in consumer finance. Changing tenor changes both your monthly payment and how much interest you ultimately pay because amortization spreads principal and interest over more or fewer months. Early in a loan, the interest portion is highest, which is why longer terms generally increase total interest.

2) Is a longer term always worse because I pay more interest?

Not always. If a longer term keeps your budget resilient, prevents missed payments, and enables penalty-free extra principal when you can, it can be smarter than a too-tight short term. The key is to compare lifetime cost and maintain flexibility to prepay or refinance when conditions improve. Build in a plan to send extra to principal and verify no prepayment penalties apply.

3) How do I quickly estimate the payment difference between tenors?

Use an amortization calculator: enter loan amount, rate, and term; you’ll see monthly payment and total interest. Run two or three terms side-by-side and export schedules. This lets you compare not only the full-term totals but also the cumulative interest for your expected holding period (e.g., 60–84 months).

4) What’s the role of APR vs the interest rate when choosing tenor?

The interest rate drives your payment; the APR includes the rate plus certain fees and points to reflect overall borrowing cost. Compare both. If you’ll keep the loan a long time, APR is a truer apples-to-apples metric; if you’ll sell or refinance in a few years, the raw payment and rate may matter more than APR because you may not “earn back” points.

5) Do prepayment penalties still exist?

Yes, but they’re regulated and less common in many mainstream mortgage products. Some loans prohibit them entirely (e.g., many government-backed mortgages), while others may allow limited penalties during the first 3–5 years. Always check your note and Ask CFPB resources to see whether penalties apply and how they’re calculated.

6) How does DTI affect the tenor I should choose?

DTI (monthly debts ÷ gross income) is a lender and self-check. If a short term pushes your DTI above typical comfort ranges, consider scaling down the loan amount or opting for a longer tenor. U.S. conventional mortgage guidelines can allow DTIs above 36% in some cases—up to 50% via automated systems with compensating factors—but higher DTIs reduce resilience.

7) Should I pay points to lower the rate if I’m picking a long term?

Maybe. Paying points raises upfront cost but can lower the rate and total interest on longer holds. If you plan to refinance or sell within a few years, the upfront spend might not break even. Ask your lender for a points vs no-points side-by-side and compute the break-even months (points ÷ monthly interest savings).

8) Are ultra-long terms (84–96 months for cars; 40 years for mortgages) ever a good idea?

They can reduce payments, but risks grow: more total interest, slower equity build, and a longer period of negative equity risk for depreciating assets like cars. For mortgages, very long terms can dramatically raise lifetime cost. If you must go long, prioritize the ability to prepay principal and avoid penalties so you can shorten the effective term over time.

9) If I choose a longer term, how much can extra payments really help?

A lot. Example: on $250,000 at 6% for 30 years (~$1,499/month), adding $250 monthly can cut about 9 years and save roughly $100,000 in interest. The exact savings depend on rate and remaining term, but consistent extra principal is one of the most powerful levers—just confirm there’s no penalty and label the payment “to principal.”

10) Do country rules change the tenor decision?

Yes. Rules on prepayment, disclosure, and underwriting vary. For instance, India’s central bank has barred prepayment penalties on floating-rate loans to individuals, increasing flexibility, while U.S. rules regulate but don’t universally ban penalties. Always check your jurisdiction’s regulator or consumer-finance agency before assuming terms.

Conclusion

Choosing loan tenor is a balancing act between today’s comfort and tomorrow’s cost. Longer terms smooth cash flow and reduce payment risk, but they add months (or years) of interest; shorter terms speed equity and lower total cost, but they demand stronger monthly capacity. The most reliable approach is to model two or three tenors, keep your DTI and emergency fund intact, and favor the shortest term you can comfortably sustain. If you need the safety of a longer term, preserve flexibility with penalty-free extra principal and a written plan to increase prepayments as your income rises. Reassess after 12 months or if rates move materially—your optimal tenor is not a one-and-done choice but a living decision tied to your goals, cash flow, and the rate environment.

Take the next step: price two tenors today, export the amortization schedules, and pick the shortest one you can keep—then automate an extra $50–$300 to principal each month.

References

- What is the difference between a mortgage interest rate and an APR? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Aug 30, 2023. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-the-difference-between-a-mortgage-interest-rate-and-an-apr-en-135/

- What is a debt-to-income ratio? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Aug 30, 2023. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-debt-to-income-ratio-en-1791/

- B3-6-02, Debt-to-Income Ratios. Fannie Mae Selling Guide (web), accessed Sep 2025. https://selling-guide.fanniemae.com/sel/b3-6-02/debt-income-ratios

- Eligibility Matrix. Fannie Mae (PDF), Aug 2025. https://singlefamily.fanniemae.com/media/20786/display

- What is a prepayment penalty? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Sep 13, 2024. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-prepayment-penalty-en-1957/

- Can I be charged a penalty for paying off my mortgage early? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Sep 13, 2024. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/can-i-be-charged-a-penalty-for-paying-off-my-mortgage-early-en-204/

- Reserve Bank of India—Pre-payment Charges on Loans Directions, 2025. RBI via FIDC (PDF), Jul 2, 2025. https://www.fidcindia.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/RBI-PRE-PAYMENT-CHARGES-02-07-25.pdf

- Amortized Loan Explained. Investopedia, updated 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/amortized_loan.asp

- What Is an Amortization Schedule? Investopedia, updated 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/amortization.asp

- How should I use lender credits and points? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Oct 19, 2023. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/how-should-i-use-lender-credits-and-points-also-called-discount-points-en-136/

- APR vs. Interest Rate: What’s the Difference? Bankrate, Jul 1, 2025. https://www.bankrate.com/mortgages/apr-and-interest-rate/

- Loan Amortization Calculator. Investopedia, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/loan-amortization-calculator-5114098