If you’re serious about building wealth, you can’t only chase returns—you have to measure and manage risk with equal rigor. The good news is that you don’t need a PhD or a Wall Street terminal to get started. This guide breaks down five practical, widely used indicators for assessing investment risk, with plain-English explanations, step-by-step instructions, quick tools you can use in a spreadsheet, and sample mini-plans you can run this week. By the end, you’ll know how to read and apply volatility, beta and correlation, drawdowns, Value at Risk (and Expected Shortfall), and liquidity indicators to make more resilient decisions.

Disclaimer: This article is educational and does not constitute financial advice. Investment circumstances are unique—consult a qualified financial professional for personalized guidance.

Who this is for: DIY investors, finance students, early-career analysts, and anyone who wants a concrete framework for evaluating portfolio risk without getting lost in jargon.

What you’ll learn: The five essential risk indicators, how to calculate them in a spreadsheet, how to interpret them in context, the common mistakes to avoid, and exactly how to weave them into a simple four-week implementation plan.

Key takeaways

- Volatility (standard deviation) shows how widely your returns swing. It’s the baseline indicator for “how bumpy” an investment ride tends to be.

- Beta and correlation reveal how much a position tends to move with markets or other assets—crucial for diversification and stress mapping.

- Drawdowns capture the size and duration of past peak-to-trough losses—the most intuitive “gut-check” of real-world pain.

- Value at Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES) estimate the scale of potential losses at chosen confidence levels—useful for setting limits and loss-absorption plans.

- Liquidity indicators (bid-ask spread, turnover, depth) tell you how easily you can enter/exit without moving the price—often overlooked until it’s urgent.

Volatility (Standard Deviation)

What it is and why it matters

Volatility measures how much an investment’s returns typically vary around their average. Higher volatility means a wider range of potential outcomes—both positive and negative—while lower volatility means a steadier ride. It’s the foundational indicator because it turns “risk” into a number you can compare across assets and timeframes.

Core benefits:

- Gives a single, comparable number for “bumpiness.”

- Converts neatly across timeframes (e.g., daily to annual).

- Forms the base for other risk tools (Sharpe ratios, VaR models).

Requirements, tools, and low-cost options

- Data: Historical prices (daily or monthly). You can pull from free sources or your broker.

- Tools: Excel/Google Sheets (functions like

STDEV.P/STDEV.S), or any statistical package. - Cost: Free to minimal.

- Low-cost alternative: Use prebuilt volatility calculators from reputable finance education sites if you don’t want to compute it yourself.

Step-by-step (spreadsheet-friendly)

- Collect prices: Get at least 1–3 years of daily closing prices for a stock or fund.

- Compute returns: In a new column, calculate periodic returns. For daily returns:

=LN(P_t / P_{t-1}). - Calculate standard deviation: Apply

STDEV.Sto the return series over your chosen window (e.g., last 60 trading days). - Annualize (optional): Multiply daily standard deviation by the square root of trading days in a year (commonly 252).

- Record the result: Note both the daily and annualized volatility so you can compare assets consistently.

Beginner modifications and progressions

- Simplify: Start with monthly returns to reduce noise; annualize by multiplying standard deviation by √12.

- Progress: Move to rolling windows (e.g., 20-, 60-, 120-day) to see how volatility evolves.

- Advanced: Compare realized volatility to implied volatility (from options) to gauge whether the market expects future turbulence to be higher or lower than history suggests.

Recommended frequency and metrics

- Update cadence: Weekly is plenty for long-term investors; daily for active traders.

- KPIs: Current 60-day annualized volatility; percentile—e.g., “Is today’s vol in the top/bottom 20% of last three years?”

Safety, caveats, and common mistakes

- Volatility ≠ risk for everyone. A long-term investor may tolerate volatility that would ruin a short-term trader.

- Non-normal distributions. Markets can have fat tails and clustering (quiet periods followed by storms). Don’t assume “bell curve” perfection.

- Timeframe trap. A low-vol asset can still suffer deep drawdowns (steady until it breaks). Always pair volatility with drawdown analysis.

Sample mini-plan (2–3 steps)

- Calculate 60-day and 252-day annualized volatility for your top five holdings.

- Flag any name where 60-day > 252-day by 50% or more—review position size and stop-loss or hedging plans.

Beta and Correlation (Market and Cross-Asset Sensitivity)

What they are and why they matter

- Beta estimates how much an asset tends to move relative to a benchmark (e.g., your home-market index). A beta of 1.2 suggests the asset moves about 20% more than the market on average; 0.7 suggests it’s tamer.

- Correlation (from –1 to +1) measures how two return streams move together. Low or negative correlations are the raw material of diversification.

Core benefits:

- Beta helps you understand market-linked (systematic) risk and position sizing versus your overall risk budget.

- Correlation helps you construct portfolios that don’t all fall together when stress hits.

Requirements, tools, and low-cost options

- Data: Daily or weekly returns for your asset and benchmark(s).

- Tools: Excel/Sheets (

SLOPEor regression for beta;CORRELfor correlation). - Cost: Free.

- Low-cost alternative: Many broker sites and fund factsheets publish beta. For correlation, free online tools or simple spreadsheets work fine.

Step-by-step (beta)

- Prepare returns: Compute daily (or weekly) returns for both the asset and your chosen benchmark over the same dates.

- Regression approach: Use

=SLOPE(asset_returns, market_returns)for beta. - Check R²: Run a linear regression to capture both beta and R². Higher R² means the market explains more of the asset’s movement.

- Annualize context (optional): Keep returns in consistent frequency (don’t mix daily with weekly).

Step-by-step (correlation)

- Align series: Same frequency, same dates.

- Compute: Use

=CORREL(series1, series2). - Interpret:

- +0.8 to +1.0: Move together strongly.

- +0.3 to +0.7: Moderately related.

- –0.3 to +0.3: Weakly related.

- –0.8 to –1.0: Move in opposite directions strongly.

Beginner modifications and progressions

- Simplify: Start with monthly returns to get a cleaner signal.

- Progress: Use rolling correlations (e.g., 36 months) across key asset pairs (equities vs. bonds, equities vs. commodities) to see how diversification changes over time.

- Advanced: Estimate downside correlation (only on negative-return days) to understand crisis co-movement.

Recommended frequency and metrics

- Update cadence: Monthly or quarterly for strategic portfolios; weekly for active multi-asset allocators.

- KPIs: Portfolio weighted-average beta; pairwise correlations between your top five holdings; rolling 36-month stock/bond correlation if you hold both.

Safety, caveats, and common mistakes

- Correlation is not static. It often rises toward 1 during market stress (“when it rains, it pours”). Build buffers.

- Beta is backward-looking. Regimes change. Re-estimate after big macro shifts or business model changes.

- Benchmark choice matters. A tech stock’s beta to a broad market may understate its sensitivity to a tech index.

Sample mini-plan (2–3 steps)

- Compute 36-month rolling correlations among your main asset classes.

- If any pair’s correlation has drifted above +0.7, look for an alternative with lower correlation to restore diversification.

Drawdowns (Peak-to-Trough Loss and Duration)

What they are and why they matter

A drawdown is the percentage drop from a portfolio’s prior peak to a subsequent trough. Maximum drawdown (MDD) is the worst of these drops over a period. Duration measures how long it took to recover back to the old high. These are the most intuitive, “lived experience” indicators of risk.

Core benefits:

- Translates risk into “how much could I have been down?”

- Highlights path dependency—steady losses feel very different than a quick dip and rebound.

- Informs cash needs, rebalancing discipline, and psychological readiness.

Requirements, tools, and low-cost options

- Data: Historical portfolio or fund values (daily or monthly).

- Tools: Excel/Sheets with a cumulative return column, a running maximum, and a drawdown column.

- Cost: Free.

- Low-cost alternative: Many fund research sites publish historical drawdowns—use them to set expectations before you buy.

Step-by-step (spreadsheet)

- Compute cumulative returns: From start date, compound periodic returns to build a portfolio “equity curve.”

- Track running peak: In the next column, use a running

MAXformula to track the highest equity value so far. - Drawdown series:

Drawdown = (Equity / RunningPeak) – 1. - Maximum drawdown: Take the minimum of the drawdown series.

- Duration: Count periods from the start of the drawdown until the equity curve exceeds the prior peak.

Beginner modifications and progressions

- Simplify: Start with monthly NAVs for a fund; move to daily when comfortable.

- Progress: Analyze sector-level drawdowns and contribution—which positions aggravated the worst episodes?

- Advanced: Add Ulcer Index or pain ratio to capture both depth and duration of declines.

Recommended frequency and metrics

- Update cadence: Monthly is enough for most.

- KPIs: Current drawdown, 10-year maximum drawdown, and time-to-recover statistics.

Safety, caveats, and common mistakes

- Not predictive. A low historical MDD doesn’t guarantee a gentle future.

- Horizon mismatch. A short history can hide structural risks.

- Path sensitivity. Same annual return can come with very different journeys. Don’t compare funds solely on returns—compare drawdown profiles.

Sample mini-plan (2–3 steps)

- Calculate 10-year max drawdown and max duration for your portfolio (or longest available).

- If MDD exceeds your comfort threshold (e.g., –25%), adjust allocation or add a rule for staged de-risking when losses hit specific levels.

Value at Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES)

What they are and why they matter

- Value at Risk (VaR) estimates the threshold loss you should not expect to exceed over a specified period at a given confidence level. Example: “1-day 95% VaR of $10,000” means that on 19 out of 20 days, losses shouldn’t exceed $10,000.

- Expected Shortfall (ES)—also called Conditional VaR—estimates the average loss beyond that VaR threshold. It focuses on tail risk: “If things get that bad—or worse—how bad is ‘bad’ on average?”

Core benefits:

- Translates risk into money and time units investors understand.

- Useful for setting limits, margin buffers, and cash reserves.

- ES is particularly informative for stress periods and heavy-tailed distributions.

Requirements, tools, and low-cost options

- Data: Return history for your portfolio/asset.

- Tools: Excel/Sheets for historical VaR/ES; or use variance-covariance (parametric) approximations; or run simple Monte Carlo simulations.

- Cost: Free to do in a spreadsheet; open-source libraries if you code.

- Low-cost alternative: Many brokers and portfolio tools show a basic VaR—verify assumptions before relying on it.

Three common methods (with steps)

A) Historical simulation (robust for beginners)

- Gather a clean return series (e.g., last 1–5 years of daily returns).

- Sort returns from worst to best.

- For 95% VaR, take the 5th percentile (the value at the index equal to 5% of observations).

- ES: Average all returns worse than that percentile.

- Multiply by current portfolio value to convert to currency.

B) Variance–covariance (quick, assumption-heavy)

- Compute mean and standard deviation of returns.

- Choose confidence (e.g., 95% corresponds to a z-score of ~1.65 under normality).

- VaR ≈ z × volatility × portfolio value (adjust sign).

- ES has a closed-form under normality but is more sensitive to tail assumptions.

C) Monte Carlo (flexible, more effort)

- Fit a distribution (e.g., normal, t-distribution) to your returns or specify factor shocks.

- Simulate many return paths (e.g., 10,000).

- Compute VaR and ES across the simulated distribution.

Beginner modifications and progressions

- Start simple: Use historical VaR/ES first; it makes minimal assumptions.

- Progress: Compare historical VaR to parametric VaR—if they diverge sharply, investigate non-normality and regimes.

- Advanced: Incorporate time-varying volatility (e.g., GARCH) or stress windows (e.g., 2008, 2020) to get “regime-aware” tail estimates.

Recommended frequency and metrics

- Update cadence: Weekly or monthly for investors; daily for risk-sensitive trading.

- KPIs: 1-day and 10-day 95% and 99% VaR; corresponding ES; number of VaR exceptions (how often actual losses breach VaR) in backtests.

Safety, caveats, and common mistakes

- Assumption blindness. Parametric VaR underestimates tails if returns are skewed or fat-tailed.

- False precision. A two-decimal VaR is still an estimate—treat it as a decision aid, not a prophecy.

- Backtesting matters. Track exceptions; if actual breaches exceed expectations, recalibrate or switch methods.

- Horizon mismatch. Don’t scale short-horizon VaR to longer periods without validating the square-root-of-time assumption.

Sample mini-plan (2–3 steps)

- Compute 1-day 95% historical VaR and ES for your portfolio using the last three years of daily returns.

- Set a soft limit at ES and a hard limit at VaR for position sizing (e.g., “If ES exceeds 1.5% of equity, reduce gross exposure until it falls below 1%.”).

Liquidity Risk Indicators (Bid-Ask Spread, Turnover, Depth)

What they are and why they matter

Liquidity risk is the possibility you can’t trade quickly at a fair price. It shows up as wider bid-ask spreads, thin market depth, low turnover, and slippage when your order moves the market. Liquidity dries up exactly when you need it most, amplifying losses.

Core benefits:

- Helps you avoid “paper profits” that vanish when you try to sell.

- Improves execution planning and position sizing.

- Reduces forced selling and margin stress during market shocks.

Requirements, tools, and low-cost options

- Data: Realtime or end-of-day quotes (bid, ask, last), average daily dollar volume, and sometimes Level II depth-of-book (if available).

- Tools: Broker dashboards, public filings/factsheets for funds, and simple spreadsheets.

- Cost: Free to minimal.

- Low-cost alternative: If you can’t see depth, approximate liquidity with average daily dollar volume and percentage bid-ask spread.

Step-by-step (practical checks)

- Bid-ask spread (%):

(Ask – Bid) / Midpoint × 100. A smaller percentage indicates tighter liquidity. - Turnover / ADV: Compare your intended trade size to average daily dollar volume (ADV). A rule of thumb is not to exceed 10–20% of ADV in a single day for smaller names.

- Slippage test: For thin assets, use limit orders in small tranches to measure the market impact before scaling up.

- Holding vehicle check: For ETFs or funds, inspect underlying holdings. An ETF may trade actively while its underlying basket is illiquid—spreads can widen in stress.

Beginner modifications and progressions

- Simplify: Track just the percentage spread and ADV for each holding.

- Progress: Add effective spread (based on actual execution vs. midpoint) and order book depth if your broker provides it.

- Advanced: Estimate implementation shortfall across your trades to quantify the full cost of getting in/out.

Recommended frequency and metrics

- Update cadence: Check before each trade; review portfolio-level liquidity monthly.

- KPIs: Median percentage spread, fraction of positions where proposed trade size <10% of ADV, worst-case spread during past stress windows.

Safety, caveats, and common mistakes

- Don’t rely on calm-day spreads. In volatility spikes, spreads gap wider, and depth vanishes.

- ETF mirage. Liquid wrapper, illiquid contents—understand what you actually own.

- Chunking orders. Large market orders in thin names can move prices sharply. Use limits and tranche execution.

Sample mini-plan (2–3 steps)

- Add two columns to your portfolio sheet: percentage spread and ADV.

- Set a rule: Avoid new positions where spread >0.5% and trade size >10% ADV unless you have a compelling reason and a staged execution plan.

Quick-Start Checklist

- Pick your benchmark (broad market index) for beta estimates.

- Gather price data (preferably at least 3 years of daily prices).

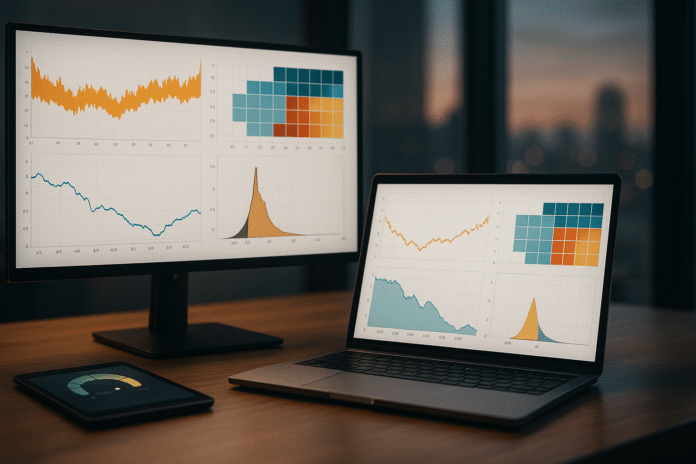

- Build a spreadsheet with tabs for Volatility, Beta/Correlation, Drawdowns, VaR/ES, and Liquidity.

- Decide on rolling windows (e.g., 60-day for trading, 252-day for strategic).

- Define thresholds/limits, e.g., “Max 1-day 95% VaR of 1.25% of equity,” or “No new position with spread >0.75%.”

- Schedule a monthly risk review to update metrics and rebalance.

Troubleshooting & Common Pitfalls

- Mismatched frequencies: Mixing daily asset returns with weekly benchmark returns distorts beta and correlation. Align your data.

- Short histories: A calm two-year window can understate true risks. Add stress windows (e.g., 2008, 2020) for perspective.

- Over-reliance on a single indicator: Volatility says nothing about liquidity; drawdown ignores frequency of losses; VaR hides tail severity without ES. Use the set.

- Hidden concentration: Low correlation today might rise in a crisis. Add position and sector caps and rehearse what you’ll cut first.

- Scaling mistakes: Don’t blindly use square-root-of-time scaling across big horizons. Validate with historical data.

- Ignoring costs: A “cheap” small-cap may not be cheap after slippage and spreads. Track implementation shortfall.

How to Measure Progress (Risk KPIs that Actually Move)

- Stability of volatility: Is your 60-day portfolio volatility within your target band (e.g., 8–12% annualized)?

- Tail control: Are VaR exceptions roughly in line with your chosen confidence level? If 95% VaR is your yardstick, exceptions should be near 5% over time—not 10–15%.

- Crisis readiness: Do you maintain a pre-defined de-risking staircase (e.g., cut gross by 20% if drawdown >10%) and have you tested it against historical episodes?

- Diversification quality: Are rolling correlations among your top holdings stable and below your ceiling (e.g., <0.6)?

- Liquidity hygiene: What fraction of your holdings can you fully exit in two trading days without exceeding 20% of ADV? Track this as a portfolio-level metric.

A Simple 4-Week Starter Plan

Week 1 — Build your risk dashboard

- Set your benchmark and collect 3–5 years of daily prices for your holdings and the benchmark.

- Create tabs for Volatility, Beta/Correlation, Drawdown, VaR/ES, and Liquidity.

- Compute baseline: 60- and 252-day volatility; portfolio beta; pairwise correlations; 10-year (or longest) max drawdown & duration; 1-day 95% historical VaR and ES; spreads and ADV.

Week 2 — Set limits and rules

- Define risk limits: max position beta, max 1-day VaR as % of equity, acceptable spread thresholds, and minimum diversification criteria (e.g., no single sector >25%).

- Add conditional formatting to your sheet to flag breaches automatically.

Week 3 — Stress test & rehearse

- Recreate stress windows (e.g., pandemic shock) and re-run your metrics on that subset.

- Run a tabletop exercise: “If the portfolio hits –10% drawdown, what gets trimmed first? How fast?”

Week 4 — Implement and monitor

- Adjust positions to bring metrics within limits.

- Schedule a monthly 60-minute review to update all five indicators and log any policy exceptions (and their outcomes).

FAQs

1) What’s the single most important indicator to start with?

Volatility. It’s simple, comparable across assets, and a foundational input for several other measures. Pair it with drawdown for a reality check.

2) How much history do I need for reliable estimates?

More is better, but 3–5 years of daily data is a practical minimum. For tail metrics like VaR/ES, include major stress periods when possible to avoid “calm bias.”

3) Should I use daily or monthly returns?

Daily captures nuance but is noisy. Monthly is cleaner for long-term asset allocation. Many investors compute both: monthly for strategy, daily for monitoring.

4) My correlations spiked during a selloff—did diversification fail?

Diversification weakens under stress because correlations often rise toward 1. Plan for that by holding some assets with different risk drivers and by setting de-risking rules.

5) Is VaR “dangerous” or outdated?

VaR is useful if you understand its limits (distribution assumptions, scaling). For tail awareness, complement it with Expected Shortfall and scenario stress tests.

6) Can I rely on published betas from my broker?

They’re fine as a starting point, but definitions vary (lookback window, frequency, benchmark). If a position matters, compute beta yourself and update on a schedule.

7) What’s a “good” volatility or drawdown level?

There’s no universal good/bad. It depends on your time horizon, cash needs, and psychology. A retiree may target <10% annualized portfolio volatility; a young accumulator can accept more if compensated by expected return.

8) How often should I recalculate these indicators?

Monthly is sufficient for long-term portfolios. Traders may update daily. Always refresh after regime-changing events (policy shifts, crises, major earnings surprises).

9) Do I need fancy software?

No. You can compute everything in a spreadsheet. Over time, you might adopt specialized tools for convenience, but the logic is portable.

10) What if my portfolio is mostly funds?

Use fund price history, factsheets (for volatility, beta), and research tools (for drawdowns). For liquidity, check the fund’s underlying holdings, not just the ETF’s own trading activity.

11) How do I know if my VaR model “works”?

Backtest exceptions. If your 95% 1-day VaR is breached far more than 5% of the time, your model is underestimating risk—change assumptions or methods.

12) Can I ignore liquidity if I’m buy-and-hold?

You can de-emphasize it, not ignore it. Liquidity vanishes in crises. Even long-term investors occasionally need to rebalance or raise cash—plan for execution.

Conclusion

Risk isn’t the enemy—unmeasured risk is. With five indicators—volatility, beta/correlation, drawdowns, VaR/ES, and liquidity—you can quantify different angles of danger, set practical limits, and prepare playbooks before markets test your resolve. You’ll make fewer reactive decisions, stay invested through rough patches that match your plan, and cut exposure when your data—not your emotions—tell you it’s time.

Copy-ready CTA: Open your spreadsheet, compute these five indicators for your top holdings today, and schedule a monthly 60-minute risk review—your future self will thank you.

References

- How Is Standard Deviation Used to Determine Risk?, Investopedia, updated 2015. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/021915/how-standard-deviation-used-determine-risk.asp

- Standard Deviation Formula and Uses, Investopedia, updated 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/standarddeviation.asp

- Volatility: Meaning in Finance and How It Works With Stocks, Investopedia, updated 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/volatility.asp

- How Do You Calculate Volatility in Excel?, Investopedia, updated 2014. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/021015/how-can-you-calculate-volatility-excel.asp

- What Beta Means for Investors, Investopedia, updated May 30, 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/beta.asp

- How Beta Measures Systematic Risk, Investopedia, updated 2015. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/031715/how-does-beta-reflect-systematic-risk.asp

- Correlation: What It Means in Finance and the Formula, Investopedia, updated 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/correlation.asp

- Protecting Portfolios Using Correlation Diversification, Investopedia, updated 2008. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/financial-theory/09/uncorrelated-assets-diversification.asp

- Maximum Drawdown (MDD): Definition and Formula, Investopedia, updated 2015. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/maximum-drawdown-mdd.asp

- Minimum capital requirements for Market Risk, Bank for International Settlements (Basel Committee), January 2019. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d352.pdf

- Risk Measurement: An Introduction to Value at Risk, Casualty Actuarial Society (Linsmeier & Pearson), 1996. https://www.casact.org/sites/default/files/old/specsem_99frmgt_pearson2.pdf

- VALUE AT RISK (VAR), Aswath Damodaran (NYU Stern), 2007. https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/pdfiles/papers/VAR.pdf

- RiskMetrics™—Technical Document (Fourth Edition), J.P. Morgan/Reuters, 1996. https://www.phy.pmf.unizg.hr/~bp/TD4ePt_5.pdf

- The Sharpe Ratio, William F. Sharpe (Stanford), n.d. https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/sr/sr.htm

- sharpe-lecture.pdf (Nobel Lecture), William F. Sharpe, 2016. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/sharpe-lecture.pdf

- Access to Capital and Market Liquidity (Study), U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (DERA), 2017. https://www.sec.gov/files/access-to-capital-and-market-liquidity-study-dera-2017.pdf

- Volatility (finance), Wikipedia, updated 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volatility_%28finance%29

- Beta (finance), Wikipedia, updated 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beta_%28finance%29

- Fundamental Review of the Trading Book, Wikipedia, updated 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_Review_of_the_Trading_Book

- How To Convert Value At Risk To Different Time Periods, Investopedia, 2004. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/04/101304.asp

- Options Volatility: The VIX, Rule of 16, and Skew, Charles Schwab, Feb 22, 2023. https://www.schwab.com/learn/story/options-volatility-vix-skew-and-rule-16

- Understanding the ‘Rule of 16’ in Plain Terms, Options Industry Council, July 2025. https://www.optionseducation.org/news/understanding-the-rule-of-16-in-plain-terms