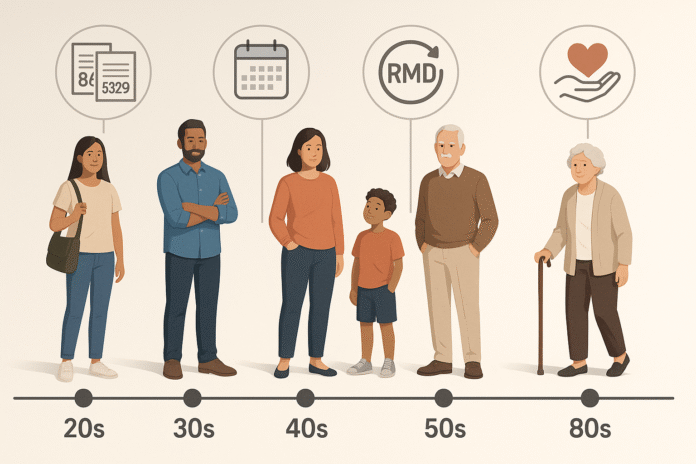

A Traditional IRA can be a powerful, flexible way to save for retirement—but the rules change as your life does. This guide walks you through the most common missteps people make in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and beyond, and shows you how to avoid them so you keep more of what you’ve saved. If you’re building or drawing down a Traditional IRA, you’ll learn the decisions that matter most, the deadlines that bite, and the tax forms that keep you out of trouble. Quick take: A Traditional IRA is a tax-deferred account; for now you can contribute up to $7,000 ($8,000 if you’re 50+) and deductibility depends on your income and workplace plan status. As of now, RMDs generally begin at age 73 for most savers.

This article is educational, not tax or investment advice. Talk with a qualified professional about your specific circumstances.

1. Assuming You Can’t Contribute Because You Have a 401(k)

You can contribute to a Traditional IRA even if you’re covered by a retirement plan at work; the confusion is about the deduction, not the contribution. Many early- and mid-career savers skip IRA contributions entirely after they enroll in a 401(k), thinking they’re “ineligible.” That mistake can cost years of tax-deferred growth or an immediate deduction you otherwise deserve. The IRS rules separate eligibility to contribute (almost anyone with compensation can, up to the annual dollar limit) from eligibility to deduct (which phases out at certain income levels if you or your spouse is covered at work). Practically, that means you might contribute and take a full deduction, a partial deduction, or no deduction at all—yet the contribution itself can still go in and grow tax-deferred. If you’re in a high bracket today and don’t qualify for a deduction, it may still be strategic to contribute (then consider conversion planning) rather than forgo IRA space entirely.

1.1 Why it matters

- Contribution eligibility is broad; skipping it loses tax-advantaged space you can’t retroactively reclaim.

- Deduction phase-outs change as income or marital status changes; you might be eligible this year even if you weren’t last year.

- Non-deductible contributions without a plan (or without Form 8606—see Item 4) create future tax complexity.

1.2 How to do it

- Check the dollar limits: For now the IRA contribution limit is $7,000 ($8,000 if 50+).

- Verify deduction status: If you or your spouse is covered at work, your IRA deduction may be reduced or disallowed based on modified AGI.

- Still contribute if useful: Consider funding even when non-deductible if you have a sensible conversion or long-term plan.

Mini-checklist

- Confirm you have compensation equal to or greater than the amount contributed.

- Look up your workplace coverage and MAGI to see whether your contribution is deductible.

- Document your choice (deductible vs. nondeductible) for tax filing.

Sources to ground this: IRS contribution limits and deduction rules clarify that contributions are allowed even when a plan at work exists; deduction may phase out with income.

2. Missing the Contribution Window (and Waiting Too Long to Fund)

You can make an IRA contribution for a tax year up to your tax-filing deadline (not including extensions)—but waiting until April often means missing months of compounding, and missing the deadline entirely costs you the year. Many savers plan to “catch up later,” only to have life intervene. Funding earlier (even monthly) can add thousands over a career because dollars work longer. The fix is simple: know the window for the year you’re funding and automate your schedule so contributions actually happen. For now taxes, your IRA contribution window runs from January 1, 2026 through the unextended federal tax deadline in 2026. If you realize you’ve overcontributed or contributed for the wrong year, you usually have until your return due date (including extensions) to withdraw the excess and avoid a 6% excise tax.

2.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Contribution timing: “Tax return filing deadline (not including extensions)” governs IRA contribution due dates.

- Late fix: Excess contributions generally can be corrected by the due date of your return, including extensions, to avoid the 6% excise.

- Compounding edge: Funding early means more months invested each year—small habits, big differences by retirement.

2.2 Steps that work

- Auto-fund monthly from your checking account starting in January.

- Tag the year with your custodian each time (e.g., “contribution”).

- Calendar a reminder 30 days before tax day to top off.

Close-out: Don’t wait to “see how the year goes.” Put a schedule to work for you and let the calendar be your ally, not your adversary.

3. Overlooking the Spousal IRA When One Partner Has Little or No Income

A common mid-life oversight: households with one earner assume the non-earning spouse can’t fund an IRA. In fact, as long as you file a joint return and have enough joint taxable compensation, both spouses can contribute to separate IRAs up to the annual limits. That effectively doubles your available IRA space and can be especially valuable during caregiving years or career breaks. People miss this because they think IRA contributions are tied to an individual’s pay stub; they’re not—joint compensation supports both spouses’ IRA contributions. The spousal IRA also interacts with deduction rules: whether each spouse’s contribution is deductible depends on workplace coverage and income. Plan ahead so you don’t leave contribution room unused in years when a deduction is available.

3.1 How to use it

- Eligibility: File Married Filing Jointly and have joint taxable compensation.

- Limits: For now, each spouse can contribute $7,000 (or $8,000 if 50+), subject to the household’s compensation cap.

- Deduction check: If either spouse is covered by a plan at work, the deduction may phase out; verify before filing.

3.2 Mini-checklist

- Open a separate IRA for the non-earning spouse (ownership is individual).

- Confirm total IRA contributions across both spouses don’t exceed joint compensation or twice the annual limit.

- Track who contributed what for tax reporting.

Wrap-up: The spousal IRA turns one income into two retirement nest eggs—don’t leave that space empty.

4. Making Nondeductible Contributions but Failing to File Form 8606

Nondeductible IRA contributions are perfectly legal—but if you don’t file Form 8606, the IRS won’t know you already paid tax on that basis, and you may get taxed again on withdrawal. This mistake often happens when income is too high for a deduction or when people prepare their own taxes without software nudges. The fix is discipline: any year you make a nondeductible contribution, file Form 8606 to record your basis; keep copies forever. You’ll need that basis to prorate future distributions and conversions so only the earnings and pre-tax amounts are taxed. If you missed filing in a prior year, you can generally file a standalone Form 8606 to correct your records.

4.1 Why it matters

- Without 8606, the IRS assumes $0 basis and more of your future withdrawals look taxable.

- Accurate basis also matters for Roth conversions and backdoor Roth strategies (next item).

4.2 Tools & tips

- Form 8606 (and its instructions) explain how to track basis and report conversions and distributions.

- Keep a simple spreadsheet that matches what you report on 8606 each year.

- If you switch tax preparers, provide prior 8606s so your basis isn’t “lost.”

Example: You contribute $6,000 nondeductible in 2023 and $7,000 and now —your $13,000 basis should be on file. Converting $10,000 from an IRA with a $50,000 total balance means only 20% ($2,000) of the conversion is tax-free, because the pro-rata rule aggregates all IRAs.

5. Ignoring the Pro-Rata Rule on Backdoor Roth Conversions

The backdoor Roth—making a nondeductible Traditional IRA contribution and then converting it—can be smart for high earners. The gotcha is the pro-rata rule: the IRS treats all your Traditional, SEP, and SIMPLE IRAs as one bucket for conversion taxes. If you have pre-tax dollars anywhere in those IRAs on December 31, a proportional share of your conversion is taxable—even if the dollars you converted came from a nondeductible contribution. Many people do the contribution and conversion but forget about old rollover IRAs from a prior job, then get a surprise tax bill. The most reliable way to minimize tax on a backdoor Roth is to move pre-tax IRA dollars into your current employer plan (if permitted) before year-end so your “IRA bucket” is mostly basis when you convert.

5.1 How the math bites

- Suppose your total IRA balances on December 31 are $95,000 pre-tax and $5,000 basis. If you convert $5,000, only 5% is tax-free; 95% is taxable income.

- The snapshot date is December 31—balances that day control the pro-rata calculation, not the day you convert.

5.2 Guardrails

- Consolidate pre-tax IRAs into a 401(k)/403(b) before December 31 if your plan allows inbound rollovers.

- Keep documentation and ensure Form 8606 reflects the basis and conversion.

- Consider doing the contribution and conversion in quick succession to limit market movement.

Bottom line: Backdoor Roths work best when your IRA “bucket” is clean; otherwise the pro-rata rule will slice off a taxable chunk.

6. Overcontributing (or Contributing Without Compensation) and Not Fixing It Promptly

Excess contributions happen more often than you think—after a raise, a bonus, or a year with lower compensation than expected. Contributing when you don’t have enough taxable compensation for the amount, or exceeding the annual cap, triggers a 6% excise tax each year the excess remains. The good news: if you spot it early, you can withdraw the excess (and associated earnings) by your tax return due date, including extensions, and usually avoid the excise. People get into trouble by ignoring custodian notices or assuming the error will “wash out next year.” It won’t—excesses linger and compound penalties if you don’t correct them.

6.1 Fix-it flow

- Identify the excess (e.g., contributed $8,000 at age 45).

- Request a return of excess contribution from your custodian for the correct tax year; remove allocable earnings.

- Amend if needed and keep records; use Form 5329 if the excise applies.

6.2 Quick numbers

- Current limit: $7,000 (under 50) or $8,000 (50+).

- Excess removal deadline: due date of your return, including extensions.

- If you miss the window, expect a 6% excise tax each year until corrected.

Synthesis: Excesses don’t fix themselves—act before filing (or by extension) and document the correction so the 6% doesn’t haunt future years.

7. Taking Early Withdrawals Without Planning for the 10% Additional Tax

Pulling money before age 59½ generally triggers a 10% additional tax on top of ordinary income tax unless an exception applies. Emergencies happen, but many early withdrawals are avoidable with better planning—HSA funds, emergency savings, or borrowing options might be cheaper. When withdrawals are unavoidable, learn the exceptions (certain medical costs, disability, first-home up to certain limits for IRAs, higher-education costs, qualified birth/adoption, and 72(t) SEPP payments, among others). If you claim an exception, you typically report it on Form 5329. Mistakes here include assuming all exceptions that apply to 401(k)s apply to IRAs (they don’t), or starting a 72(t) schedule without understanding its rigidity.

7.1 Exceptions snapshot (not exhaustive)

- Qualified higher-education expenses (IRAs).

- First-time homebuyer distributions up to statutory limits from IRAs.

- Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (72(t))—must follow the method for the required term.

- Certain medical expenses above thresholds; disability; birth or adoption payments.

7.2 Practical steps

- Before tapping an IRA early, compare all options’ after-tax costs.

- If you use an exception, document it and file Form 5329 correctly.

- For 72(t), model multiple calculation methods and commit to the schedule.

Takeaway: Early withdrawals are expensive by default; know your exceptions and paperwork so you don’t pay more than you must.

8. Botching Rollovers: Breaking the 60-Day Rule, the Once-Per-Year Rule, or Triggering Withholding

Rollover errors are classic—and costly. If you take possession of IRA funds, you generally must deposit them into another IRA within 60 days or the amount becomes taxable (and potentially penalized). You can do only one such 60-day IRA-to-IRA rollover in any 12-month period across all your IRAs, regardless of how many you own. Worse, distributions paid to you from an IRA are generally subject to 10% federal withholding unless you opt out—so even if you redeposit the check, you may be short. The cleanest path is a trustee-to-trustee (direct) transfer or a direct rollover so you never touch the money. If you miss the 60-day window, limited IRS self-certification or waiver relief may apply for circumstances beyond your control, but don’t rely on it.

8.1 Do this instead

- Choose trustee-to-trustee transfers or direct rollovers whenever possible.

- Avoid indirect rollovers that require you to redeposit funds within 60 days.

- Track your once-per-12-months usage; it applies in aggregate across all IRAs (Traditional, SEP, SIMPLE, Roth).

8.2 Numbers & rules

- 60-day redeposit clock starts the day after receipt.

- Once-per-year limit applies to IRA-to-IRA rollovers (not to direct transfers or plan-to-IRA rollovers).

- 10% default withholding on IRA distributions paid to you unless you elect out.

Wrap-up: Keep your hands off the check. Direct movement avoids withholding, the 60-day trap, and the once-per-year limitation headaches.

9. Mis-Timing RMDs at Age 73 (and Not Fixing Misses the Right Way)

For most IRA owners, required minimum distributions (RMDs) start the year you turn 73. You can delay the first RMD until April 1 of the following year, but then you’ll owe two RMDs that calendar year (the delayed first plus the current year). People often trip here—either by forgetting the first one or by bunching two in a high-income year and inflating their tax bill. If you miss an RMD, today’s law generally imposes a 25% excise tax on the shortfall (potentially reducible to 10% if you correct within two years and file Form 5329 requesting relief). Custodians can calculate RMDs, but you’re responsible for taking them; get on a schedule and revisit beneficiaries while you’re at it.

9.1 Smart timing choices

- If your income will be lower next year, consider delaying your first RMD to April 1 to bunch two into the lower-income year (less common).

- If next year will be higher, take the first RMD before Dec 31 of the year you turn 73 to avoid doubling up.

- Automate quarterly withdrawals to smooth cash flow and withholding.

9.2 Fixing a miss

- Take the missed amount as soon as discovered.

- File Form 5329 and request the excise tax reduction (or relief when applicable).

- Keep custodian letters and calculations with your records.

Key references: IRS RMD FAQs and news guidance reflect the age-73 rule and the reduced excise tax with timely correction.

10. Missing Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) After Age 70½

From age 70½, you can make Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) directly from your IRA to eligible charities and exclude up to an indexed annual limit from your income. QCDs can satisfy part or all of your RMD once you reach 73, lowering taxable income and potentially reducing impacts on bracket creep, Social Security taxation, and Medicare thresholds. Many retirees overlook QCDs or donate from checking accounts instead, losing the unique income-exclusion benefit. As of now, the QCD limit is $108,000 per person (indexed; a separate one-time election up to $54,000 exists for certain split-interest gifts). Get the details right: the check must go straight from your IRA to the charity; donor-advised funds don’t qualify.

10.1 How to execute cleanly

- Ask your custodian for a QCD check or direct transfer payable to the charity.

- Keep the charity’s acknowledgment letter for your records.

- Coordinate QCDs before taking taxable RMDs.

10.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Annual QCD cap: $108,000 per individual (indexed).

- Split-interest one-time election: up to $54,000 within the QCD rules.

- Age: Available once you’re 70½—not merely the year you turn 70½.

End note: If you already give, QCDs can stretch generosity and tax efficiency at the same time.

11. Neglecting Beneficiary Designations and the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule

Beneficiary choices affect how (and how fast) your IRA must be distributed after your death. Under current rules, most non-spouse beneficiaries must empty an inherited IRA within 10 years of the original owner’s death (with some exceptions). Spouses have more flexible options (e.g., spousal rollover, treating as their own), while certain eligible designated beneficiaries (minor children, disabled/chronically ill individuals, and those within 10 years of the decedent’s age) can use life expectancy payouts. Common mistakes: never naming beneficiaries, failing to update after marriage/divorce, or assuming all heirs can “stretch” distributions. Also note transitional IRS relief for certain years—another reason to keep paperwork current and heirs informed.

11.1 Practical steps

- Name primary and contingent beneficiaries and review them annually and after life events.

- For complex family situations, consider trusts and get legal advice; trust wording must match IRA rules.

- Educate adult children on timelines so they’re not scrambling mid-grief.

11.2 Why it matters

- The wrong (or missing) designation can force faster distributions, higher taxes, and probate delays.

- Keeping documents updated is one of the highest-ROI “paper” tasks you can do.

Source check: IRS beneficiary guidance explains the 10-year rule and categories of beneficiaries with different payout options.

12. Forgetting Age-Based Opportunities: The $1,000 Catch-Up and Other Milestones

Your IRA has age-based milestones that should trigger action. At age 50, you’re eligible for a $1,000 catch-up contribution (bringing your cap to $8,000). At age 70½, QCDs become available (Item 10). At age 73, RMDs begin (Item 9). Missing these milestones means saving less than you can, paying more tax than necessary, or scrambling at year-end. Many savers don’t increase contributions at 50 because the dollar amount seems small; over 15–20 years, the extra $1,000 per year plus compounding is significant. Put your milestones on a timeline—then automate increases and set reminders for the first RMD year.

12.1 Milestone map

- Age 50: Add $1,000 catch-up (Traditional or Roth IRA).

- Age 70½: Turn on QCDs to reduce future RMD-taxable income.

- Age 73: Begin RMDs (with the option to delay the first to April 1 of the following year).

12.2 Implement it

- Auto-increase IRA contributions the month you turn 50.

- Add a QCD plan to your giving once you’re 70½.

- Run a 5-year tax forecast before RMD age to smooth brackets.

Close-out: Your IRA has a built-in calendar. Use it to save more, give smarter, and withdraw on your terms.

FAQs

1) What’s the Traditional IRA contribution limit?

For now, you can contribute up to $7,000 if you’re under 50, or $8,000 if you’re 50 or older. The limit applies across all of your IRAs (Traditional + Roth) combined. Your deduction for a Traditional IRA may be limited if you or your spouse is covered by a retirement plan at work and your income is above certain thresholds.

2) When is the deadline to make a IRA contribution?

You generally have until the unextended federal tax filing deadline in 2026 to make a IRA contribution. That “tax day” rule (without extensions) governs IRA deadlines. Contributing earlier in the year gives you more months invested, which can boost long-term growth.

3) Can I contribute to a Traditional IRA if I already have a 401(k)?

Yes. Participation in a workplace plan does not block you from contributing to a Traditional IRA. It may limit whether the contribution is deductible on your tax return; check the IRS deduction charts for your filing status and income. Even without a deduction, some savers still contribute to pursue a backdoor Roth conversion.

4) What is Form 8606 and why does it matter?

Form 8606 tracks nondeductible contributions (your “basis”) and reports Roth conversions and certain distributions. Without it, you risk paying tax again on money you already taxed. File it for any year you make nondeductible contributions or do conversions, and keep copies with your permanent records.

5) I accidentally overcontributed. How do I fix it?

Contact your IRA custodian and request a return of excess contribution for the correct tax year. Do this by your tax return due date (including extensions) to avoid a 6% excise tax; otherwise, the excise can apply each year until you correct it. Keep all custodian statements for your records, and use Form 5329 if needed.

6) What’s the difference between a transfer and a rollover?

A trustee-to-trustee transfer (or direct rollover) moves funds directly between custodians—you never touch the money and there’s no 60-day clock. An indirect rollover pays you first; you must redeposit the funds in 60 days and you get only one such IRA-to-IRA rollover in any 12-month period. Transfers avoid default withholding and most pitfalls.

7) When do RMDs start, and what if I miss one?

RMDs generally start the year you turn 73. You may delay the first until April 1 of the following year (but then you’ll take two that year). If you miss an RMD, an excise tax of 25% applies to the shortfall (potentially reducible to 10% with timely correction); file Form 5329 to request relief.

8) How do QCDs work, and what’s the limit?

If you’re 70½ or older, you can make Qualified Charitable Distributions directly from your IRA to eligible charities and exclude the amount from income. QCDs can count toward your RMD once you’re 73. For now, the limit is $108,000 per person, indexed for inflation; a separate $54,000 one-time amount applies for certain split-interest gifts.

9) What is the saver’s credit and who qualifies?

The Retirement Savings Contributions Credit (Saver’s Credit) is a nonrefundable credit worth up to $1,000 ($2,000 if MFJ) for eligible contributions to retirement accounts. Income limits adjust annually; for now, the top income thresholds increased from 2024 levels—check current IRS tables to confirm your eligibility before filing.

10) Can I fund an IRA for a non-earning spouse?

Yes—if you file Married Filing Jointly and have sufficient joint taxable compensation, each spouse can fund their own IRA up to the annual limits. Deductibility depends on plan coverage and income. This “spousal IRA” is an easy way to double a household’s IRA saving capacity.

Conclusion

Traditional IRAs reward clear, consistent decisions—and punish procrastination and paperwork gaps. Early in your career, the big wins are simple: fund on time, capture the saver’s credit if you qualify, and don’t assume workplace coverage eliminates IRA opportunities. In your peak-earning years, the nuances matter more: understand deduction phase-outs, file Form 8606 when you go nondeductible, and master the pro-rata rule before attempting a backdoor Roth. As retirement nears, execution becomes everything: move money with direct transfers, avoid the once-per-year rollover trap, and fix overcontributions before penalties attach. In retirement, timing and tax planning dominate: manage RMDs deliberately, use QCDs to align giving with tax efficiency, and review beneficiaries so heirs don’t face avoidable taxes.

Pick two actions to implement today—set up automatic monthly contributions and schedule a beneficiary review—then add one life-stage tactic (saver’s credit, 8606 audit, or QCD plan) this quarter. Small, timely moves compound into real money. Ready to audit your IRA in 30 minutes? Open your statements, pull last year’s tax return, and complete the mini-checklist from the sections above—then make one improvement you can automate.

References

- Retirement Topics — IRA Contribution Limits, IRS, updated Nov 1, 2024 & Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-ira-contribution-limits

- IRA Deduction Limits, IRS, updated Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/ira-deduction-limits

- 401(k) Limit Increases to $23,500 for 2025; IRA Limit Remains $7,000, IRS Newsroom, Nov 1, 2024.

- Traditional and Roth IRAs — When Can I Contribute? IRS, updated Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/traditional-and-roth-iras

- IRA Year-End Reminders, IRS, updated Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/ira-year-end-reminders

- About Form 8606 (Nondeductible IRAs), IRS, July 9, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-form-8606

- Rollovers of Retirement Plan and IRA Distributions, IRS, Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/rollovers-of-retirement-plan-and-ira-distributions

- Retirement Plans FAQs Relating to Waivers of the 60-day Rollover Requirement, IRS, Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plans-faqs-relating-to-waivers-of-the-60-day-rollover-requirement

- Retirement Topics — Exceptions to Tax on Early Distributions, IRS, Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-exceptions-to-tax-on-early-distributions

- Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (72(t)), IRS, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/substantially-equal-periodic-payments

- Retirement Plan and IRA Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs): FAQs, IRS, updated Dec 10, 2024 & 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plan-and-ira-required-minimum-distributions-faqs

- IRS Urges Many Retirees to Make Required Withdrawals… (Penalties for Missed Distributions), IRS Newsroom, Dec 10, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-urges-many-retirees-to-make-required-withdrawals-from-retirement-plans-by-year-end-deadline

- Give More, Tax-Free: Eligible IRA Owners Can Donate up to $105,000 in 2024 (and $108,000 in 2025), IRS Newsroom, Nov 14, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/give-more-tax-free-eligible-ira-owners-can-donate-up-to-105000-to-charity-in-2024

- Internal Revenue Bulletin 2024-47 (QCD Amounts Indexed for 2025), IRS, Nov 18, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/irb/2024-47_IRB

- Retirement Savings Contributions Credit (Saver’s Credit), IRS, updated Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-savings-contributions-credit-savers-credit

- 2025 Saver’s Credit Income Limits (News Release), IRS, Nov 1, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/401k-limit-increases-to-23500-for-2025-ira-limit-remains-7000

- Retirement Topics — Beneficiary, IRS, Aug 26, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-beneficiary