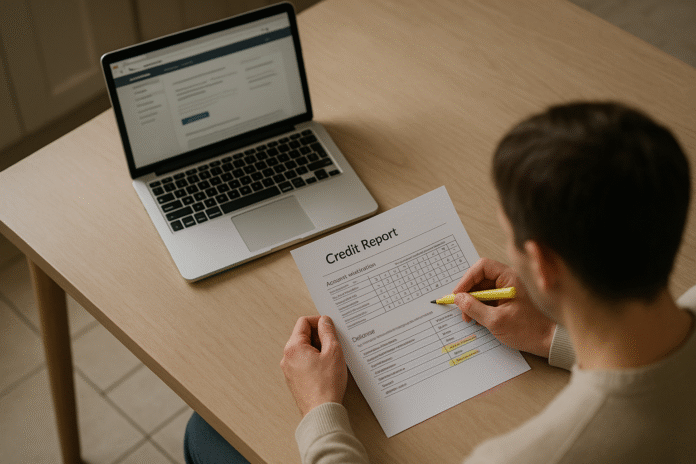

If you’ve ever opened your credit report and wondered what each line from a bank, card issuer, auto lender, or mortgage company really means, you’re in the right place. This guide walks you through how to read the lender-supplied entries on your credit report—often called tradelines—so you can check for accuracy, understand the story they tell, and decide what to do next. “Credit report statements from lenders” are the account records those lenders furnish to credit bureaus and that bureaus display as tradelines with balances, limits, dates, remarks, and payment history. As of now, you can still access frequent free reports in many regions; this article explains how to use them effectively. Quick note: this is educational, not financial or legal advice; consider professional guidance for your situation.

Below are 12 clear, sequential steps. Each shows you what to look for, how to interpret it, and the practical actions you can take right away.

1. Verify Your Identity Details and Report Date First

Start by confirming the report belongs to you and is current. Check your name variations, current and past addresses, date of birth, and the last four digits of your Social Security number (or national identifier, where applicable). The first lines of a credit report also show the report date—the snapshot moment bureaus pulled your data together—and sometimes a “date updated” for each account. If the identity section has errors or outdated addresses that aren’t yours, it can hint at mixed files or identity theft and may also affect matching when lenders pull your file. A quick identity check avoids chasing problems that stem from the wrong file.

A correct identity section sets the baseline for everything else you’ll read. If the report date is several weeks old, don’t panic—most tradelines update monthly, and a balance right after a statement cut may look higher than what you owe today. In the U.S., you can request reports from all three bureaus (Equifax, Experian, TransUnion) and compare; small differences are normal, but big discrepancies deserve attention. In the UK and Canada, your report will likely show similar personal data maintained by local credit reference agencies (CRAs). If something is off, note it now so your later dispute letter is complete.

Mini-checklist

- Name spelling/aliases match your official ID

- Current address accurate; past addresses recognizable

- Report “as of” date noted (write it at the top of your notes)

- Employer field (if present) looks familiar

- Any unknown address or name? Flag for potential dispute

Why it matters

Identity mismatch can cascade into accounts misattributed to you or, worse, fraud signals. Fixing basics first avoids rework and strengthens any future dispute. Close this step by confirming you’re reading the right person’s report on the right date.

2. Match Each Tradeline to a Real-World Account You Know

The quickest way to demystify a report is to map each line to the account you actually use. A tradeline lists the creditor name (sometimes abbreviated), masked account number, type (revolving/installment/mortgage/other), credit limit or original loan amount, current balance, payment history grid, and remarks. Because creditor names may appear as payment processors or portfolio names, build a crosswalk: “SYNCB/AMAZON” might be your Amazon store card, while “TD BANK USA/CC” might be a co-branded card. If you don’t recognize a lender, check your files for welcome emails, monthly statements, or mobile apps tied to the issuer.

Create a simple table linking report name → your nickname (e.g., “AmEx Blue”), opened date, limit/original amount, and current balance. This map helps you spot duplicates across bureaus and identify any truly unknown account. If an account seems unfamiliar, it may be a collection, a transferred/closed tradeline after refinancing, or a sign of identity theft. For authorized user accounts, ensure they’re appropriately labeled and reflect expected history.

How to do it

- Pull all three reports (where available) to triangulate unusual abbreviations.

- Search email for “Welcome,” “Statement ready,” or creditor names.

- Compare last four digits of the masked account number to your card/app.

- For auto loans and mortgages, match the original loan amount and opened date to closing documents.

Mini case

You see “ALLY FINANCIAL” with an original amount of $24,800 opened 05/2022. That matches your auto loan paperwork—mapped and verified. A second “ALLY/LEASE” opened 08/2022 you don’t recognize? That’s a red flag to investigate.

Finish this step with a one-page map; you’ll reference it in every later step.

3. Decode Account Type and Terms (Revolving vs. Installment vs. Mortgage)

Interpreting the account type correctly anchors everything else you read. Revolving accounts (credit cards, lines of credit) have credit limits and variable balances; installment loans (auto, personal, student) show an original amount and declining balance; mortgages are installment loans with property-secured terms and unique remarks. Some reports also show open accounts (due in full monthly, less common for consumers) and other/retail categories. Each type has different scoring implications and different “healthy range” indicators (e.g., utilization matters on revolving but not on installment).

Read the terms fields: for revolving, confirm the credit limit; for installment, note original amount, scheduled payment, and months term (if listed). If a revolving account shows “no limit,” it may be a charge card or not reported; in that case, bureaus may use a high balance field as a proxy in some models. For mortgages, watch for adjustable-rate flags or forbearance remarks that clarify why balances changed.

Numbers & guardrails

- Revolving utilization target: often <30% overall; many consumers aim for <10% for score optimization.

- Installment loans: focus isn’t utilization; instead verify you’re current and the balance is amortizing as expected.

- Mortgages: expect large balances; focus on on-time payment history and accurate status.

Common mistakes

- Treating installment balances like revolving utilization (they’re scored differently).

- Missing a hidden deferred student loan status that later becomes due.

- Assuming a “no limit” card has unlimited spending; it may simply be unreported.

The right type/terms context helps you judge what looks “healthy” in the following sections.

4. Read the Payment History Grid and What Late Codes Mean

The payment history grid condenses 24–36+ months of status into month-by-month codes. Start by scanning for anything other than “OK” or “C”/“0” (varies by bureau). Codes like 30/60/90 indicate days past due; “CO” can indicate charge-off; “L” may denote late (format varies). One isolated 30-day late from two years ago is different from a string of recent 60s/90s. The most recent 24 months tend to weigh more in many scoring models, though all derogatory marks have defined lifespans.

Confirm the Date of First Delinquency (DoFD) if an account went to collections or charged off; that date controls how long negative info stays (often up to 7 years in the U.S.). If you entered a hardship program or deferment, look for remarks like “Paying as agreed under plan” or “Deferred”; those notes explain why the grid may show “OK” during relief periods.

How to analyze quickly

- Read left-to-right for recent months; mark any non-OK cells.

- Note the worst recent status within the last 24 months.

- For any 60/90+, capture the first month it occurred; that’s your timeline anchor.

- If a collection/charge-off exists, record the DoFD from the tradeline or collection entry.

Mini example

If your card shows OKs except one “30” in 06/2024 and back to OK after, you likely have a single late mark. If 06/2024 is “60” and 07/2024 “90,” your account went seriously delinquent—expect a larger score impact and stricter lender responses.

Close by listing each tradeline’s late-code summary; it’ll power your dispute or goodwill plan.

5. Understand Balances, Limits, and Utilization (and Why Timing Matters)

For revolving accounts, utilization = balance ÷ credit limit. Scoring models often penalize high utilization at both the account level and overall. Because most lenders report your balance as of the statement closing date, your report can show a high balance even if you pay in full each month. That’s why people aiming for an upcoming mortgage sometimes pay cards down before the statement cuts. For installment loans, there’s no “utilization” in the same sense; instead, verify that balances decline reasonably with each payment (unless you’re still in an interest-only phase).

Check overall utilization (sum of all card balances ÷ sum of limits) and per-card utilization. One card at 85% can hurt even if the overall is 20%. Ensure each card’s limit is reported; if it’s missing, models may use a high balance proxy, potentially inflating utilization. Some secured cards initially report small limits; that’s fine, but be mindful of how quickly they can look “maxed out.”

Practical steps

- Calculate overall and per-card utilization; target <30% overall and per card, with <10% for optimization.

- If prepping for a major loan, pay down cards 5–7 days before statement cut to control reported balances.

- Ask issuers to correct missing limits or consider a credit line increase (soft pull preferred).

- Avoid closing your oldest low-utilization card right before a major loan shopping period.

Numeric example

Card A limit $5,000, balance $1,000 (20%); Card B limit $1,500, balance $1,200 (80%). Overall utilization is ($2,200 ÷ $6,500) ≈ 34%. Even if you pay $300 total, paying Card B to $450 (30%) reduces both overall and the harmful single-card spike.

Finish by scheduling pay-downs relative to statement dates—timing is leverage.

6. Interpret Account Status: Open, Closed, Paid, Transferred, or Charged Off

Status fields condense the life story of an account. Open/Current means the line is active and paid as agreed; Closed—Paid indicates you (or the lender) closed it in good standing; Transferred/Sold appears when debt moves to another servicer; Charged Off means the lender wrote the debt off as a loss (it may still be collectible); In Collection indicates a collection agency is now reporting. For mortgages and student loans, you may also see Forbearance, Deferment, or Rehabilitation statuses that change scoring impact and next steps.

Match status to what truly happened. Refinanced a car? The original tradeline should close as “Transferred” or “Paid,” and a new loan opens with the new lender. If a card was closed by the credit grantor, the report should say so; that matters because some lenders view “closed by grantor” differently than “closed by consumer.” For charge-offs, confirm the DoFD and any amounts listed as past due.

Tools/Examples

- When a card is closed, verify the limit no longer affects utilization but the history may still count.

- If a charged-off debt was later settled, look for “Settled for less than full balance”—accurate but negative.

- If a debt is sold, expect a zero balance on the original tradeline and a separate collection entry.

Mini-checklist

- Status matches your records and dates

- No active account mis-labeled “closed by grantor”

- Charged-off amounts and DoFD recorded; collection balances not duplicated on original line

Clear, accurate status lines prevent double-counting negatives and support clean underwriting.

7. Decode Remarks and Special Codes (Metro 2® and Bureau Glossaries)

Besides plain-English labels, reports include remarks and internal codes defined by the industry’s Metro 2® standard. You might see notes like “Consumer disputes this account,” “Natural disaster/forbearance,” “Debt buyer account,” “Paid in full,” “Account in investigation,” or status codes that look cryptic. While consumers don’t need the full codebook, knowing that remarks exist—and that they carry meaning for lenders and scoring models—helps you verify whether an account is being portrayed fairly.

If a remark doesn’t match your situation, dispute it. For example, if a deferment ended, the “deferred” remark should be removed after normal reporting resumes. If you’ve filed a dispute, the “XB”/in dispute equivalent remark (wording varies) should appear while the investigation is ongoing; models often ignore an account’s negative impact during that period. After resolution, the remark should update again. For government or student loan programs, specific remarks denote rehabilitation or forbearance, explaining why no late codes appear for several months.

How to do it

- Use each bureau’s glossary or help pages to translate codes and remarks.

- Keep screenshots or PDFs of before/after when a remark should change.

- If a collector reports “paid collection,” ensure the original creditor tradeline shows zero balance and a transfer/closure remark to avoid double negatives.

Mini example

You completed a disaster forbearance on a mortgage. The report still shows “Affected by natural/declared disaster—Forbearance” six months later. That’s outdated. File a targeted update request: the remark should now reflect normal repayment.

Reading remarks ensures your story is told accurately, not just technically.

8. Distinguish Hard vs. Soft Inquiries—and Use Rate-Shopping Windows Wisely

Hard inquiries appear when you apply for credit; they can shave a few points off your score and typically remain on your report for two years (most scoring impact fades after 12 months). Soft inquiries—like checking your own report, pre-qualified credit card offers, or existing creditor reviews—don’t affect your scores and appear only to you. Understanding which is which helps you time applications and minimize score dings.

For certain loans (mortgage, auto, student), most modern models group multiple hard pulls within a defined rate-shopping window as a single event for scoring. As of now, guidance commonly cited is 14–45 days, depending on the model. The safest approach is to cluster official applications tightly (e.g., within 14 days) and keep them for the same loan type and similar amounts. Credit card applications generally don’t benefit from this grouping.

Practical tips

- Batch mortgage/auto/student loan applications within 14 days to fit all models; 30–45 days can still be fine for many.

- Use pre-qualification (soft pull) to narrow card options before a hard inquiry.

- Monitor reports to verify that soft checks (e.g., existing creditors’ periodic reviews) aren’t mis-classified as hard.

- Don’t fear one well-timed inquiry; excessive, scattered hard pulls are the problem.

Mini example

You’re shopping auto loans. You apply with three lenders between October 5 and October 10. Scoring models that honor rate-shopping treat those as one inquiry event for score impact, protecting your rating while you secure the best APR.

Handled well, inquiries become a tool—not a landmine—when reading and planning from your report.

9. Cross-Check Across Bureaus and Spot Data Mismatches

It’s normal for Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion to have slight differences because not all lenders furnish to all bureaus at the same time. Your task is to spot material mismatches: an account present on one but missing on another, different opened dates, inconsistent limits, or divergent payment history for the same months. A missing credit limit at one bureau can inflate utilization there, creating inconsistent scores across lenders who pull different bureaus.

Create a three-column comparison for each tradeline: present? (Y/N), limit/original amount, balance, worst recent status, remark differences. If one bureau shows a late that the others don’t, dig into statement evidence to prove it wrong. If you recently refinanced or transferred an account, expect a lag. Mark follow-up dates to re-check after a full reporting cycle.

Why it matters

Lenders often pull one bureau. You could be approved by a lender who checks Experian but denied by one who checks TransUnion if a single data error lives there. Proactive cross-checking reduces that risk.

Steps to resolve

- Dispute bureau-specific errors with that bureau and, when necessary, the data furnisher (the lender).

- Attach the same evidence package to each dispute to keep records aligned.

- After resolution, pull follow-up reports to confirm synchronized corrections.

Consistent files across bureaus make your applications smoother and outcomes more predictable.

10. Evaluate Major Negative Events: Collections, Charge-Offs, Repos, and Bankruptcies

Not all negatives are equal. Collections indicate a third party is trying to recover a debt; charge-offs are lender write-offs; repossession/foreclosure relates to collateral; bankruptcies are legal proceedings with unique reporting timelines. When you see these, read DoFD, current balance, and responsibility (individual, joint, authorized user). For collections, confirm whether they’re paid or unpaid; paid collections may still appear but are often treated differently by modern scoring models, depending on type and date. Medical debt rules vary by region and have evolved over time; check current local guidance.

If a charge-off is sold, the original lender’s tradeline should show zero balance with a remark indicating transfer, while the collector reports the amount due. Never pay both; a double-paid record is hard to unwind. For secured debts, repossessions and foreclosures come with dates (sale/auction, deficiency balances) you should verify against your paperwork.

Tools/Examples

- Build a timeline: last on-time payment → first delinquency → charge-off/collection placement → payments/settlement.

- For bankruptcy, confirm the chapter, case number, filing/discharge dates, and which tradelines were included.

- For medical collections (where applicable), check current bureau policies on dollar thresholds and reporting eligibility.

Mini example

A $1,050 telecom bill appears as a collection opened 03/2024 with DoFD 12/2023. You paid it 08/2024. Ensure the collector now reports paid and that the original provider’s tradeline shows $0 and “transferred/sold,” not a lingering past-due amount.

Approach these entries with precision; clarity here yields the biggest score and underwriting improvements.

11. Master the Timeline of Dates: Opened, Reported, Last Payment, DoFD

Dates tell underwriters whether a problem is old and resolved or recent and risky. Key fields include Date Opened, Date Reported/Updated, Last Payment Date, Date Closed, and the DoFD for derogatories. An account opened a decade ago helps your length of credit history; a brand-new card can temporarily reduce your average age. A “recently updated” date with a normal OK status simply indicates fresh reporting; a “recently updated” date that adds a late mark signals a new issue.

Build a quick date timeline per tradeline. If you’re preparing for a major loan, avoid closing old accounts right before applying; that may shorten your average age. If you’ve just paid a large balance, allow one full reporting cycle for the new low balance to hit all bureaus. For collections or charge-offs, the DoFD controls the removal clock in many jurisdictions (often around 7 years in the U.S.); it generally shouldn’t be re-aged by subsequent collection activity.

Mini-checklist

- Opened date aligns with your records

- Last payment and reported dates make sense given your recent activity

- DoFD captured for any derogatory tradeline

- No evidence of re-aging (e.g., DoFD shifting forward without cause)

Example

You settled a collection on 06/2025; the DoFD remains 02/2023. The collection’s updated date becomes 06/2025 (that’s normal), but the removal timeline still counts from 02/2023, not the settlement date.

When the dates make sense, your file tells a coherent, credible story.

12. Turn Insights Into Action: Disputes, Goodwill, Pay-for-Delete, and Monitoring

After you understand the entries, act methodically. Use your notes to decide whether to dispute, request a goodwill adjustment, negotiate a pay-for-delete (where permitted), or simply monitor. Disputes are for inaccuracies—wrong balances, misapplied lates, mixed files. Goodwill is for accurate but isolated mistakes (e.g., one 30-day late after years of on-time payments). Pay-for-delete is a negotiation with a collector (not original creditors) to remove a collection entry in exchange for payment; policies vary by collector and region.

Bundle each action with evidence: statements, payment confirmations, emails, settlement letters. Send disputes through the bureau portals or by mail with tracking; escalate to the furnisher (lender/collector) if needed. For goodwill, write a concise, respectful letter explaining the context and your clean history. For pay-for-delete, get written confirmation before paying. Finally, set up ongoing monitoring and calendar reminders to pull your reports every few months (or weekly where free) and before major applications.

Mini action plan

- Dispute: Identify each error, attach proof, state desired correction, follow up in 30–45 days.

- Goodwill: Request late-mark removal citing strong history and the specific cause.

- Pay-for-delete: Negotiate in writing with collectors; confirm bureau removal terms before paying.

- Monitor: Use official free sources; save PDFs and keep a version history.

Example

You find a misreported 60-day late from 04/2024. You submit a dispute with your bank’s on-time payment screenshot and statement showing the correct date. The lender corrects it; your grid updates to “OK,” and your score rebounds.

A systematic approach turns insight into measurable score and underwriting improvements.

FAQs

1) What exactly are “credit report statements from lenders”?

They’re the tradelines that lenders (credit card issuers, banks, auto and mortgage lenders, student loan servicers) furnish to credit bureaus. Each tradeline summarizes the account type, balance or credit limit, dates, payment history, and any remarks or status (e.g., open, closed, charged off). Bureaus aggregate these from many furnishers; that’s why different reports can show slight timing differences.

2) How often do lenders update my credit report?

Most furnishers report monthly, usually around your statement closing date for revolving accounts and shortly after payment cycles for installment loans. Updates can lag a cycle, especially after status changes like transfers or payoffs. If you’ve paid a large balance, allow a full cycle for all bureaus to reflect it before expecting score changes.

3) What’s the difference between hard and soft inquiries?

A hard inquiry occurs when you apply for credit and can temporarily lower your score; it typically remains on your report for two years, though the strongest impact is within 12 months. Soft inquiries—checking your own report, pre-qualified offers, employer checks with consent in some countries—do not affect your score. You’ll see soft inquiries only on your own copy of the report.

4) How can I minimize inquiry impact when shopping for a loan?

Cluster applications for mortgage, auto, or student loans within a short window (e.g., 14 days) so modern scoring models treat them as a single event. Keep them to the same loan type and amount. Use pre-qual (soft pull) for credit cards and apply only after you’ve narrowed choices.

5) My report shows a collection and an original creditor balance—am I double-counted?

You shouldn’t be. Once a debt is sold or assigned to a collection agency, the original creditor’s tradeline should show a $0 balance and a status such as transferred/sold. If both show a balance, dispute to correct; paying both could create more problems than it solves.

6) How long do negative items stay on a credit report?

In the U.S., many negative items (late payments, charge-offs, collections) can remain for up to seven years from the Date of First Delinquency (DoFD); hard inquiries up to two years. Bankruptcies have longer timelines depending on chapter. Timelines differ by country, so check local regulator guidance (e.g., UK ICO, Canada’s FCAC).

7) Does paying a collection delete it automatically?

No. Paying a collection changes its status to paid, but it may still appear on your report unless you negotiated a pay-for-delete (where permitted) or the collector/bureau policy removes certain categories (e.g., some medical debts under current thresholds in certain regions). Always get any deletion promise in writing.

8) My revolving utilization looks high even though I pay in full—why?

Reports typically capture your balance on statement day, so even a PIF (paid-in-full) user can look maxed if purchases were high that cycle. If you’re preparing for underwriting, pay down balances before the statement cuts or make a mid-cycle payment so the reported balance is lower.

9) What’s the best way to dispute an inaccuracy?

Submit a targeted dispute to the credit bureau with clear evidence (statements, confirmations, correspondence) and the exact correction requested. You can also contact the furnisher. Keep copies and note dates. Expect a response within a statutory investigation window (often ~30 days in the U.S.); follow up if the correction doesn’t propagate to all bureaus.

10) Are authorized user accounts good or bad on my report?

They can help by adding age and limit capacity, which may improve utilization and length metrics. But if the primary user pays late or maxes out, that negative history can appear on your file, too. If an authorized user account starts hurting you, you can ask to be removed; the tradeline should then drop or no longer affect your scores after updates.

Conclusion

Understanding the credit report statements from lenders is like learning to read the instruments on a cockpit: once you grasp what each dial shows—identity data, tradeline type, payment grids, balances/limits, statuses, remarks, inquiries, and critical dates—you can fly smoother, avoid turbulence, and reach your financial destination with fewer surprises. You started by validating identity and the report date, matched each tradeline to a real account, decoded types, grids, balances, and remarks, and learned how to time applications and pay-downs. You then layered in cross-bureau checks, handled serious negatives with a clear plan, and converted insight into action via disputes, goodwill, and negotiated resolutions.

From here, build a simple monthly routine: download fresh reports (where free), update your tradeline map, and set alerts for statement dates and big changes. Before major applications, run a focused tune-up: trim utilization, group necessary inquiries, and verify that remarks and dates tell a clean story. If anything looks off, escalate with precise, documented disputes. You’ve got the playbook—now use it to keep your credit file accurate, resilient, and ready for your goals. Next step: pull your latest reports and complete the 12-step checklist today.

References

- A Summary of Your Rights Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, Federal Trade Commission (FTC), (PDF, undated summary). https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/articles/pdf/pdf-0096-fair-credit-reporting-act.pdf

- Fair Credit Reporting Act (Statute Overview), Federal Trade Commission (FTC), accessed Sep 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/fair-credit-reporting-act

- Free Credit Reports (Weekly Access Announced as Permanent), FTC Consumer Advice, Jan 4, 2024. https://consumer.ftc.gov/consumer-alerts/2023/10/you-now-have-permanent-access-free-weekly-credit-reports

- AnnualCreditReport.com – Official Site, Central Source, LLC, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.annualcreditreport.com/index.action

- Getting Your Credit Reports, AnnualCreditReport.com, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.annualcreditreport.com/gettingReports.action

- Review Your Credit Report, AnnualCreditReport.com, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.annualcreditreport.com/reviewYourReport.action

- How do I dispute an error on my credit report?, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Dec 18, 2024. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/how-do-i-dispute-an-error-on-my-credit-report-en-314/

- What kind of credit inquiry has no effect on my credit score?, CFPB, Jan 14, 2025. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-kind-of-credit-inquiry-has-no-effect-on-my-credit-score-en-321/

- Understanding Your Experian Credit Report, Experian, Jun 10, 2024. https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/credit-education/report-basics/understanding-your-experian-credit-report/

- Glossary for the History Grid (Experian Report), Experian (PDF), accessed Sep 2025. https://www.experian.com/content/dam/marketing/na/assets/cis/connect/includes/glossary-for-the-history-grid.pdf

- What Is a Credit Utilization Ratio?, Equifax, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.equifax.com/personal/education/debt-management/articles/-/learn/credit-utilization-ratio/

- Understanding Hard Inquiries on Your Credit Report, Equifax, accessed Sep 2025. https://www.equifax.com/personal/education/credit/report/articles/-/learn/understanding-hard-inquiries-on-your-credit-report/